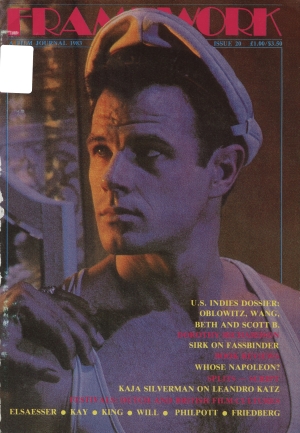

[Bild 1+2: Straub’s From the Cloud to the Resistance]

In issue 19 Don Ranvaud reviewed the 1982 Berlin Film Festival by emphasising a number of events taking place "between" the screening programmes of the festival. The article by Thomas Elsaesser below was read out at the conference organized by Framework on notions of independent cinema and presents a valuable synthesis of the concerns of our conference. It also lays the foundation for a more systematic con- sideration of the role of festivals and the relation between production/distribution/exhibition in the "independent" sector already opened up by Framework's festival debate (from issue 15/16/17) and specific articles on exhibition and distribution in Britain by Archie Tait and Tony Kirkhope in issues 13 and 14.

I want to talk about films in universities and colleges, because that is where and how I make part of my living. Hence I am talking as someone who is on the buyer's side rather than the sellers. I want to talk about a perhaps modest but to my mind significant market for independent film, and it is a market that can only be supplied via the festivals, and in particular a festival like the Forum in Berlin. But there seems to be certain considerations about how to make the best use of a festival.

We have heard about the possibilities and problems of independent film-makers. They have problems both at the production stage and at the distribution stage. And we all know how personally ruinous and also emotionally and intellectually exhausting it is to find that a film in which one has invested several years of one's life, gets shown at two or three festivals, is submerged by hundreds of others, and from thereafter has a ghost-like existence in somebody's bedroom and on funding or grant applications.

On the production side, however, we also know that in certain countries, notably West European ones, the situation has significantly improved, via forms of public funding, television, individual grants and subsidies. The bottleneck there is felt to be more acute on the distribution side. And it is here that film critics often don't make enough distinctions, and where film-makers might think about and work on more flexible strategies.

I'd like to indicate the situation as I see it, with a few rather schematic points:

-

The question of what constitutes 'independent film' ought to be looked at as much from the consumer side as from the production end. 'Independence' covers some many forms of financing today that the lowest common denominator, namely films not produced by a Hollywood or Hollywood-type production machine – is so vague and general, that it only makes a sense, if we turn the criterion round again, and agree to look at 'independent cinema' as comprising all those films which for their reception, their consumption require and demand a public, an audience, that cannot be reduced, precisely, to a single common denominator.

-

So, independent cinema for me is a cinema that demands an approach to distribution which is different – I don't mean non-commercial, but more than commercial, commercial-plus, if you like.

-

This, as we know, is happening in a variety of ways:

- a) through seasons and the acquisition of prints at the national cinemateques and regional or communal cinemas.

- b) through so-called repertory cinemas, cinemas whose programming policies are not tied to the big international distribution chains, and which, for this kind of policy in turn rely on the existence of likeminded, risk-taking and enterprising distributors. In England, some of the cinema-owners or animateurs have therefore become distributors in their own right, precisely to ensure supply of suitable films.

- c) in other cases, it is not the exhibitor, but the producer/film-maker who sets up his/her own distribution. This is time and energy consuming to such a degree that one now increasingly finds groups of independent producers getting together, in order to organize joint distribution. In England this has happened with Four Corners, Circles (a feminist film distributor), Liberation Films, and Cinema Action.

- d) and finally, this is where the contribution of a festival like the Berlin Forum is so crucial. Because it does precisely bring together in an admirably heterogeneous form, producers and distributors/exhibitors of uneven weight, uneven power and uneven influence. And it seems to me absolutely crucial that such a principle of uneven weighting, or uneven exchange ought to be maintained.

- The reasons seem to me simple:

- a) It is always said that festivals are shop-windows, and as such they treat films as commodities. True enough. But if the films are indeed "bought" at festivals (and "bought" here is used in several different senses) it is a matter of hygiene to say the least that they ought not to be consumed at a festival. And what I mean by this is that films at festivals acquire an exchange value, more or less fixed, in terms of price and prizes, status, critical or news value, etc. Their actual and potential use-values elsewhere, are yet to be however, determined, and these determinants need not, perhaps ought not to be determined at the festival or at the box office.

- So that whereas the so-called "commercial film" has a use-value which exactly converges with its exchange value – both being assessed by a strictly measurable quantity – and in what I would call, a system of even exchange – namely the highest possible box office returns in the shortest period of circulation – the use-value or rather use-values of the kind of film we are today talking about, can be and is defined by different, heterogeneous and uneven exchanges. We might say that the so-called independent film is the film which can circulate in all parts of the media-systems and the body politic, whereas the so-called "commercial film" circulates more like a St Catherine's wheel, all sparks and spluttering.

- b) We are therefore talking about films with a capacity for osmosis, capillary action, films with a social, econmic metabolism. And although in many quarters this is of course recognised, it seems to me that both producers and buyers don't always show the necessary imagination to recognize a film's particular metabolism and system of absorption and circulation. In particular it is the critics and film-teachers who often fail to recognize their own roles as immaterial 'buyers' in these circuits of transmission. But this is also partly due to the fact that film-makers themselves do not fully recognize the potential of these classes of 'buyers'. There is on both sides a tendency to think inside binary oppositions: commercial vs independent, Kinofilm vs Fernsehfilm, narrative cinema vs avant-garde, mass audience vs art-film audience, political vs personal film-making. Film-makers are caught in the same ideological schema: if they don't make it with the big distributors or the so- called big audiences, then the film becomes an act of self-expression, or self-manifestation: at any rate, it becomes closed-off from the forms of mediation that exist in society: the film says what is says what it says. We all know the political and ideological strengths and weaknesses of this position. It's a myth that independent cinema today can reach audiences "directly". But one particular drawback of such an inflexible position is that it sets up as enemies exactly those who either have the energy or are paid for doing what justifies a film's existence, namely to initiate the various processes of social appropriation and absorption. How often have I noticed at festivals the hostile and suspicious look of film-makers towards film-critics and film-scholars (for fear of giving something away) only to notice an almost abject servitude moments later when a "real potential buyer" be it from television or a distributor appears on the scene.

- c) Films are sensuous, representational, socially and economically determined objects. They have many different social and aesthetic uses, one of which is obviously to ensure the film-maker's survival as a film-maker – but this last can clearly not be its only social use. In a world where without film and television nothing officially hap- pens anymore, film-makers have an extraordinary responsibility imposed on them – to be chroniclers, historians, novelists, visual artists (and composers) all at once. As a matter of fact, they don't have any choice, they are these things all at once the minute they make films – the only question then is, how seriously do they take their responsibility, as the administrators of our collective experience, memory and imagination: for it is this capital which they mould, shape, record and put in circulation.

The small market, then, that I want to remind ourselves of, is that of the films and film-makers' long march through the invisible multiplication channels – as they are created by specialized journals, scholars, teachers, film-makers' personal appearances, seasons, and above all by (film) critical or even polemical discourses outside the usual categories of author, genre, nationality, avant-garde, experimental, etc. It seems to me that for a long time now, the independent cinema has been overvalued in all those cases where a film insisted on its uniqueness and specificity – including its political effect (which all seem to me an artificial restriction of its potential use-values) and on the other hand, the independent cinema has been undervalued as far as the efforts of both film-makers and critics are concerned in exploring and imagining a film's different social use- values (which I hope I have made clear, are not identical with its so-called shelf-life).

What does this amount to in practical terms?

- a) We need film-makers who actually talk with critics rather than take defensive action

- b) we need critics who can imagine and are alert to different entry points of a film into the social and historical imaginery

- c) we need to make full use of the verbal and audiovisual technology to contextualize and cross-relate films with each other and with other cultural or documentary evidence

- d) we need to put, by whatever means, the multipliers in a position where they have both the information and practical skills to bring films alive by exploiting a film's dimensionality and heterogeneity, its different modes of appropriation.

Films are consumed not only insofar as they are seen but also insofar as they are talked about, because insofar as they occasion discourse, word, – they enter into precisely the discourses that constitute the imaginary whose existence the cinema feeds and sustains. To translate a film, to transform it in the minds of an audience, this is its mode of permanence and survival

To sum up:

-

Independent films ought to be around wherever people get together, because their particular strength is heterogeneity, which means that their power lies in the way they focus the attention of an audience on the one hand, and - on the other - release creative energies outside and in spite of the occasions that give rise to them. The good thing about an independent film is the degree to which every spectator can stil see a different film.

-

In order for this to happen, we need:

- a) more ad-hoc exhibitors (cultural institutes, art galleries, public libraries, schools, colleges), more ad-hoc promoters (such as the example of local radio-stations promoting a film, as happened in Italy; or a newspaper creating a readers' debate around a film) and different target markets.

- b) more ad-hoc audiences - through exhibitions and cultural events; conferences – whether on town planning or film theory: there exists films that can centre/decentre any occasion.

- c) in literary discussion and seminars: no literature course can afford to ignore films like those of Rivette, or Straub, or Edgardo Cozarinsky.

- d) political seminars and debates in short, the independent cinema must learn to do without cinemas.

-

We need more literature and information to become available – registers, catalogues, translation of articles and interviews: the categories and classifications have to stay open and provisional: criticism has become rather sterile and stereotyped in its ways of talking about "alternative film culture".

-

Finally, and most contentious perhaps, we need to open a debate that has tended to become suppressed: films must become available more widely, and that means using the present audio-visual technology to the full. Just as there ought to be a literature (in the form of articles, etc.) circulating about the films, video-tapes, casettes, "media-packages" must stimulate the interest and curiosity that the films deserve. The videotape of a film ought to be considered not as its substitute, but as a different form in which a film can circulate. These different forms of circulation, these different modes of absorption and social appropriation are such that they energize each other, rather than compete with or destroy each other.

The independent cinema, instead of seeking to maximise and speed up filmic consumptions, must develop for its products more indirect, slower and more mediated forms of consumption. The independent cinema, in charge of the film with a slower pulse must try to feed those parts of the body politic and aesthetic that have gone numb under the blows that the commercial cinema deals to its audiences' solar-plexus.

Thomas Elsaesser

Berlin, January 1982