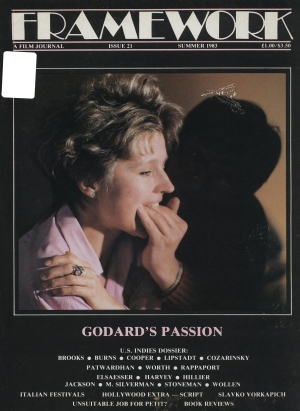

DISCOURSE AND HISTORY: ONE MAN'S WAR

AN INTERVIEW WITH EDGARDO COZARINSKY

Interview conducted by Thomas Elsaesser, Berlin 1982/Paris 1983

[Bild 1]

TE: You made OMW in France at a time when there had already been an extensive public discussion about the French and their collective memory of the 2nd WW and German occupation. The Sorrow and the Pity, Lacombe Lucien and The Last Métro among others had very much fixed the critical debate around the question of collaboration and resistance. Your film deliberately displaces these terms, and one could imagine an equally important debate around the use you make of documentary material – in your case, newsreels of the period – and the choice of a German writer, Ernst Jünger, as intimate witness. Does the question of Jünger' s complicity, his attitude to the historical events he observed, engage you more than "the truth" about the French?

EC: Whether the majority of the French collaborated or resisted is a question of statistics and a neuralgic point in the national conscience. What mattered to me was the question of Jünger the writer, and the quality of his look at history. He approaches current history with a precise surgical hand, almost as if the events he is describing are part of natural life. He works hard at having a perspective. He puts himself at a distance from what he is experiencing as if he were a visitor from another planet.

TE: No doubt, for you, OMW is also part of a different history, if only that of your other films.

EC: The question of perspective relates to something I tried to do in my previous film, The Sorcerer's Apprentices, where it is present in the use of "inserts" from a future point in time. It was introduced by the use of titles: "let's try and remember what it was like in the last third of the twentieth century", an introduction which proposed a point of view to the spectator, the vision of an unknown, unforseeable future which was established only in those written inserts. The action itself was superficially realistic, according to the conventions of the film noir, but it occasionally opened up to include excerpts of Büchner's Danton's Death, excerpts which are themselves fragments from the myth of the Revolution. This kind of formal relationship did not actually come to mind when I was working on OMW; only afterwards when I was trying to work out the fascination of Jünger's perspective.

TE: Once again, a writer's attempt to make literature a reference point outside politics and history?

EC: It represents what I believe to be the capacity of most intellectuals – to be cool, to look at things from a distance. Being aware of it, and often having a bad conscience about it, they have shown themselves, in the last half-century, overzealous to "commit" themselves, to take a stand, to do anything that might cancel that distance. To the point of wanting to be the stars of History, not its chroniclers. And that distance, when repressed, only comes back the more strongly, in the midst of political engagement. For instance, hundreds of European writers signed the protest for Régis Debray when he was imprisoned in Bolivia, and he knew they were signing for him, not for the hundreds of other people im- prisoned in the same gaol. The case of Jünger is extreme – a Reich officer in occupied Paris allowed himself to write from the point of view of an intellectual analyzing extraordinary moral, social and historical upheavals in contemporary society as if he was not a part of it.

TE: Are you saying that the exceptional circumstances of Jünger finding himself in Paris, and the disavowal of this exceptionality in his journals, manifest a general predicament of the intellectual in the face of politics?

EC: I feel it to be exemplary because it is so extreme. It casts light on our own experience, and I personally feel it as an Argentinian. When I lived in Argentina under successive but similar military regimes, there was always this understanding in intellectual circles that everybody was against the Regime. At the same time being almost a question of manners, this agreement represented an extraordinary level of passive collaboration – it meant that you did nothing about the situation. And yet, literature seems to thrive under such circumstances ....

TE: If Jünger's look as a writer was that of an alien from another planet, of someone who perceived events and upheavals as part almost of natural history, does this hard, mineral quality of his commentary not stand in a very deliberate, not to say cruel opposition to the sometimes frivolous, frothy material you have chosen from the newsreels, at least in the first "movement" of the film?

EC: When I first started on the project I had an "experimental" attitude to the work. I had the newsreels on the one hand and the Jünger journals on the other and I wanted to see what happened when they came together. Most of my preoccupations were formal (if I had no interest in form I would be doing TV reportage or magazine articles instead of films). I did not know exactly what the end result would be but I knew it would reveal something, I trusted my instinct in choosing as well as in editing: I watched the material in the archives in November and December 1980, I began editing in May 1981 for twelve weeks. After a moment of despair when I thought it would be a five hour film, I felt the material asked to be thought it would be a five hour film, I felt the material asked to be grouped in four different units, the four movements of the film. I grouped in four different units, the four movements of the film. I became very involved in the material during this time and I connected the emotional agitation I felt with my distrust of documentary and the ideology of cinéma vérité or direct cinema (I am only interested in "cinéma indirect", if it exists). The material was very much connected with my personal background in Argentina as well as my approach to the cinema.

[Bild 2: One Man’s War]

TE: One might say that the intellectual Right during this century has been preoccupied with the "disappearance of history", whereas the Left, sensing that history was very much in the making, has been obsessed with causes and effects, with instrumentality. Is your film concerned with what has happened to our concept of history during the last fifty years?

EC: I began to feel that the film was as much about today as about the past. And not simply because of the fact that I was watching the material for so many hours a day that it became a part of reality – I didn't see daylight at all! The first association I made was with the attitude of French intellectuals on the left, that "turncoat" quality of French intellectual life which is a kind of farce accepted by everybody. Nobody feels they have to justify it, changing sides and changing factions just out of a feeling that they have to move with the times. Paris fashion, which is an industry, is a model for all kinds of cultural activities, people wear certain ideas which change as fashions change. Look at the shifts of position of magazines like Tel Quel, the whole itinerary from promoting "cultural revolution" to supporting Soviet dissidents is not based so much on political analysis or gruesome discoveries but derived from a deeply ingrained intellectual frivolity.

TE:…..?

EC: Look at Sartre. He spent the Occupation writing his philosophical magnum opus and trying his hand at the theatre (I wonder if he had to sign one of those affidavits, quoted in The Last Métro, stating that to his knowledge there was no Jewish blood in the family . . . they were asked, it seems, from everybody connected with show business). Then, as if to make up for lost time, he engaged in a non-stop series of public utterances, trying in vain to leave an imprint on the making of History, being wrong more often than not, incarnating the "next-revolution-will-be-the-good-one" syndrome. Of course he was deadly serious about it all, but the results were not too far from the flippancy of the Tel Quel ideologues.

TE: Could it not be said that a preference for Jünger over Sartre today is itself an effect of fashion? Not so long ago, on the occasion of his 87th birthday, Jünger was the subject of a two-page interview in Libération, the post-68 newspaper that Sartre himself helped to found.

EC: My choice of Jünger*s point of view was not a question of preference for a Right-wing perspective, but of quoting a patently "foreign" point of view on the Paris I knew and felt I would have approached, more normally, from the Left. It was always in proportion to the capacity I knew so well to be a silent accomplice on the Left, that I related to Jünger's experience, not because there is an exact parallel, but because he represents something that always disturbed me deeply on the Left. The "gruesome" dramatic quality of wearing a German uniform from the Third Reich makes Jünger a "figure maudite" par excellence. To relate it to my own experience – there was the widespread complicity of silence about Cuba which persisted until a few years ago. In Argentina, as in every country with a Right-wing government, it was a question of keeping silent about it in order not to play into the hands of the Régime.

TE: The price of Jünger's rock-steady gaze: isn't it always a kind of nihilism, a stoic-heroic defeatism?

EC: Yes. And the Left developed a romance with Power. Jünger, instead, has no illusions whatsoever about power, which is facile in another way – you don't react because evil is impossible to defeat, except on individual terms ... I have no answer myself, which perhaps accounts for the deep sense of malaise in the film.

TE: In opposition to Jünger's totally pessimistic, end-of-the-world attitude, you concentrate strongly on the malaise the French officials felt – making speeches expressing the hope that if the French followed the Germans' wishes, there would at least be an amelioration in conditions.

EC: Things that politicians today would never dare say. So much rhetoric that politicians coud still afford at the time … Laval saying "if the French would only trust me …” I can’t imagine Pinochet or Jaruzelski saying it in this age of marketing techniques…

TE: The opposition between the ideology and illusions of the Third Reich and Jünger’s pessimism is played down in favour of the image which fashion and kalaedoscopic newsreels give of contemporary life, against the almost linear narration from Jünger. It struck me that the visual and aural material you have chosen from the archives is as worked on as Jünger’s shaping of his experiences in the journals. The journals are very self-reflective, an inner distance negating his own role, as you say. Likewise the newsreel material does not strike one as actualité but rather as so many voices appearing from another perspective. What is interesting about the politicians is that they too, seem to speak from a distance, although it may be the distance of someone who has lost his grip on events. The malaise the film provokes stems from the sense that, as a spectator, we cannot orient ourselves. We are not given an opposition, we cannot work on simply irony, as the basis for our perspective.

EC: I'm glad you say that because one of my lines of work during the editing was to wipe out every possible "gag". I think there is a constant sense of humour in the film but no gags. The closest I came was in the sequence showing the hats made of new synthetic material presented as a triumph of collaboration, between German I.G. Farben chemists and French fashion designers. There are also a number of "rhymes" which only become apparent on further viewings. For instance Jünger says that the army had to make ovens because the officials forced to shoot the Jews in the back of the head suffered mental disorders. Later, the propaganda in the French newsreels states that the police officers, found in a common grave, were shot Moscow style in the back of their necks by terrorists, i.e. resistance fighters. Several such interior rhymes occur where opposite voices and opposite propaganda plays reflect themselves.

TE: The malaise is nonetheless never released, the irony never leaves the audience in a position of knowledge.

EC: That is why I felt that the film should end as it does. That the liberation in '44 should be seen as a kind of wake, a funeral ceremony and that at this point there should be a lyrical outburst where image and soundtrack, often following different ways throughout the film, should part for ever, to the elegiac music of Strauss.

TE: You must have thought a lot about the "voice" of the camera, as it were, because there is already heterogeneity, an area of friction between the voice-over commentary of the newsreel and the point of view from which the material is shot, without even considering Jünger's voice or that of Pfitzner's or Strauss' music.

EC: One of the reasons for my deep distrust of documentary vérité is that I'm never sure what it is a document of. The newsreels were basically very truthful about what they captured only they were truthful about things other than what they thought they were saying. Time, in a sense, is the great flashlight because now you see through the lie and everything seems obvious and apparent. There are moments when I repeat the same images but in a very different context, an example is the arrival of Heydrich in Paris. Once it is there with the original newsreel commentary, presented as the arrival of a German personality in Paris, on a par with the arrival of Winifred Wagner or Franz Lehar. He is greeted in much the same way that the others are greeted and he meets French personalities like Darquier de Pellepoix (who surfaced about three years ago in Spain), and Bousquet, the personalities of the collaboration. Then I took some shots from the sequence containing the Heydrich arrival, intercut them with black leader and put on them Jünger's comments about the fauna to be seen at the German Institute, individuals "he wouldn't touch with a barge pole". Repeating the same shots with a different editing and soundtrack shows them to be both continuous and discontinuous, constructed.

TE: Only once or twice do you show the face of a name which Jünger mentions. Voice and image in general do not come together, or rather, a literary image and a photographic image of the same referent persist side by side, each with its own connotations and provoking subtle delays in the passage from perception to idea.

EC: I knew since I first thought about the film that the soundtrack and the image should be distinct, meeting occasionally at certain points but in general diverging, even where the sound track carries the commentary of the original newsreel. I wanted to have the image and soundtrack in counterpoint, each commenting on the other. What I was most afraid of, on aesthetic grounds, was that the film would be systematic in the wrong sense, in that it would become obvious to the viewer from the start how it worked, the rest following on the same principle. I was very much afraid that the film would have a method which people could pinpoint. Even if the counterpointing of image and soundtrack could be considered a method, it works in different ways. I was very careful when organising the film into four movements that you could never predict at the beginning of a section how it was going to develop.

TE: A lot of images have been appropriated by our period as the images of Paris in the thirties and Paris under the occupation. A certain "Paris" has been constructed anew, history has been rewritten through these images. Were you conscious of not giving too many iconographic references or points of recognition to your audiences?

EC: The only such point of reference occurs very near the beginning. After the parade on the Champs Elysées there is a series of shots of German street signs which follow a kind of itinerary from the Place de la Concorde to the Opéra. I kept them as a travelogue of Paris in 1940. Instead of having the traditional kind of travelogue – "here we see these charming natives" etc, instead of a voice-over stressing the difference of the "invader" from the French population, you have one of those invaders telling how happy he is to be back in Paris. He says that perhaps he should take this opportunity to settle down in Paris, since it has been offered to him freely. He is speaking as a writer who had been a frequent visitor to the city, who has friends there, favorite places, and doesn't seem to see much difference in the fact that now he is in the German army wearing a German uniform.

TE: It is as if he is on a travel grant from the German government!

EC: Exactly. Isn't it extraordinary that this "flâneur" in Benjamin's sense should be an army officer during the occupation? He is still speaking like a man of culture of the 18th century, like Voltaire going to Prussia.

[Bild 3: One Man's War]

TE: There is a strong theme concerning Europe in the film. Would you connect this to contemporary thoughts about Europe?

EC: When I was editing the film I began to think about and listen to a certain discourse of fascism in its everyday manifestations. I had previously only read literature on fascism and by fascists and, of course, I have lived in Argentina most of my life. I had always seen the aspect of caricature in fascism…

TE: Frothing at the mouth, hectoring rhetoric, ham acting …

EC: Yes, and even less directly, the idea of fascism as the counter revolution par excellence, or some Reich-inspired idea about masss hysteria. Anyway, I suddenly saw that these people were dealing with unemployment, workers from poor countries going to and being exploited by developed countries – the colonisers. There are aspects of the film which are disturbingly close to contemporary Europe. What the Third Reich tried to do – the idea of a unified Europe – was doomed because it was based in the ideas of racial superiority and a millenium mystique which were unacceptable. The idea of a unified Europe has succeeded with the EEC because it has been grounded on economic interest and the ideology of neo-capitalism which has obviously worked, up to a point.

TE: Do you agree with the assessment that fascism will be seen as the ideology of the 20th century because it did what capitalism was going to do anyway but it tried to do it too fast and with a "neo-feudal" rather than a technicist orientation. That in a sense German fascism anticipated what we are now living through but with means that were inappropriate?

EC: When I first saw the completed film I felt that there was something about it which disturbed me besides the question of fascist ideology. It was a feeling I relate to the fact that I let myself go much more in this film than in my previous work, even though it is a documentary or perhaps because it is a documentary. I let certain emotions into the film much more openly than with films I have shot myself when I was controlling things in another way. I felt the film was about the defeated, in an emotional sense – the German officers, the people of Paris, the Russian soldiers, etc. All these people were defeated but by what? Perhaps on one level they were defeated as individuals; even the people who are rejoicing at the liberation are not going to achieve power, they will be the victims of power. Also it's because they are Europeans, which connects with the constant predicament of Europe, for me the only possible place to live and yet at the same time a condemned territory. I wondered also if this period from the late 50s to the late 70s, of cultural liberality and relative lack of economic stress in Western European life, may not eventually be seen in the years to come as a belle époque. And before it, this Third Reich, hideous but at the same time realistic beyond what I would like to accept as possible. It was a very confused feeling but at the same time very acute. The images, when finally brought together, disturbed me much more, and in a way I had not expected. I thought that they would say something about the relation of an individual to his position in history and in society, and how he could deceive himself about what he was really doing. I found instead that it was saying something much wider, not so precise, but profoundly disturbing about the post-Cambodia present we're living in.

TE: Are you referring to the technological-industrial character that military engagements, especially in Latin America and Asia, have assumed in the last decade, or to the fact that the superpowers now export their wars, like their weapons and consumer-goods, to countries which cannot afford them?

EC: At the end of the film, when Jünger speaks of the attempted suicide of a fellow aristocrat and officer, he says that up to the first world war the old code of honour was still alive, but that now, the war is run by technicians. If I mention Cambodia as a turning point it is because I think it marks the end of a period when intellectuals and "politically conscious" individuals could feel safe siding with the Left. Suddenly Kissinger and China were working side by side putting the Khmer Rouge régime in power and letting it conduct the most rational genocide of recent times, and one invoking a Marxist discourse. For intellectuals, wars have always taken place elsewhere, even when they happen in their own country, but Cambodia was perhaps too much.

TE: OMW is a film by an exile about an invader, both looking at Paris from an inner distance. The newsreel material you have put together is light and ephemeral, and perhaps because of Jünger's relentlessly self-centred commentary, shot through with ironies at every point. His was an analytical mind which nonetheless doesn't necessarily believe that there is "truth" which is why the question of perspective and the look – in its wider sense – is so crucial. You emphasize this in your film, for instance by several shots of people filming, notably in the beginning, where we see a German officer – not Jünger, of course, but in some sense his double, a parody of Jünger – taking pictures with a camera. Does this not suggest that despite the polyphonic organization of many voices and multiple perspectives, the film privileges the individual voice, even if this is obviously not the voice of truth?

EC: The individual voice, of course. Junger's, not necessarily. His journals were available and the fact that his predicament (a writer and army officer, an accomplice of henchmen caring for the victims) is exceptional made him richer, more upsetting and revealing as a counterpoint. But the voices I would have liked to listen to are not those of such "stars", however engrossing their account , but those of the nameless "extras" – I have frozen the image on their faces (literally, faces in the crowd) to let us fantasize what roles they could have played, what their "one-man's-war" may have been like...

TE: It seems that despite the fact that we now live in a society of the spectacle and of the image, the literary word retains a powerful aura. Especially in the films made by writers, I have been struck by a curious effect of reversal, where the function of the images is to create a space around the words – the equivalent of the silent white margin in the printed page in a book of poems, perhaps.

EC: I find myself, in all my films so far, using black leader rather often – sometimes for rhythm, as a caesura, others to let the previous image linger a little longer on the mind, others to let words or music stand by themselves.

TE: In your film, too, the individual voice inevitably transforms the crowd of faces into abjects of a certain look, into signs for something else. Perhaps it is at this point that documentary film-making becomes a question of écriture: on the few occasions when you freeze an image, as if to point at something, you make sure that what you point to, by the technical process of interrupting the flow, retains all the ambiguity, all the irreality that such an impossible image provokes.

EC: I see the frozen images in the film as "details", such as you may find illustrating an art book. They try to stop the flow (the editing is quite fast throughout) and call attention to a gesture, to an incident, but never as explanation, rather as unexpected windows opening on something unknown. Most times I worked with them according to the music, and the music was the great organising principle of the film, not only its choices but also whether it was left under, or over, the Jünger voice or the newsreels voices, whether it runs freely for minutes or is broken in tiny units. The music suggested also that a shot be frozen at the end (the smiling girl asking a German for a cigarette) or at the beginning (the boy looking at the camera is like a still photograph suddenly brought to life – he leaves with his push cart a bombed quartier); in another case, a freeze frame in the middle of a pan shot (the close- up of a Russian prisoner looking at the sky) was placed as to coincide with a certain musical phrase.

TE: Isn't there a kind of paradox here? We do admit to a fascination of the image where the image speaks to us in an intense way and is erotic in some respects. The word speaks to us too. Yet in a sense though we are committed to a medium which speaks to us directly, it does so in an irresponsible way – we never need to know why the soldier looked, he may have been looking at a gun, etc. We have, in our fascination with the image, no responsibility to what the image "in reality" might have signified. We appropriate the image in a way that perhaps writing does not allow itself to be appropriated, for when language is used in such an appropriable way we call it bad writing, propaganda.

EC: I said to myself from the beginning that I wanted to rescue the faces of these people and preserve them. Why? To keep them for myself, perhaps. I allowed myself to engage in some kind of necrophilia by making them the object of my desire.

TE: Do you think this is an obsession which has always been in the cinema?

EC: For me its best expression is to be found in The Oval Portrait, the Poe story. In a sense that is most extraordinary thing ever to be written about the cinema.

TE: It is of course, also Fritz Lang's obsession; the creation and uncreation of those who appear on the screen. Lang, as it were, conceals his own creation in the abstractness of his mise-en-scène which is a way of starting with a blank and ending with a blank. Renoir might be seen as working in an opposite manner. He is director who uses the cinema to actually preserve a certain mode of li e, a certain sensibility and vitality. He is, as it were, on the side of life perceiving the cinema as a legitimate way of preserving it. On the other hand, Fritz Lang is on the "demonic" side, the side of power and pessimism; his cinema is about the power of the image and the power of undoing the reality which the image presumes to preserve.

EC: I did indeed feel this desire to possess – the frozen images. I started to phantisize about these people and to think what their lives might be like. I knew this was pointless but I couldn't prevent myself, it was a kind of sorcery. I think this reflects too this Lang quality, cinema as a "demonic" art. It is something, which as I said, I relate very much to Poe. I saw a film not long ago, a medium-length film made in France by the Vietnamese film-maker Lam-Le, entitled La rencontre des nuages et du dragon. It is a story about a man who embellishes the photographs of dead people so that they may enter eternal life looking at their very best. For the occupation forces in Vietnam, the French in the 50s and the Americans in the 60s, this practice is tantamount to falsification of documents and identity papers. He goes to gaol. The film tells the story of his revenge on the people who sent him to gaol, using his magic brush. It's an extraordinary film considering it was made in France on a very tight budget – it was all shot in Paris, and the banlieue becomes Saigon in the 60s. Everything is believable in the sense that von Sternberg's China and Spain (on the other end of the production scale) are believable. The story is at once about an individual's revenge and the revenge of a repressed culture on the occupying forces. But is is also a story about the cinema, the power of the image; the embellishing power, not just of an actor's face but the fact that the cinema creates out of that image an immortality. As in Poe, the cinema in general changes the people who work on it and the image does destroy the owner in the end.

TE: This even affects documentary.

EC: Yes. As far as documentary is concerned, I always feel that fiction films are the best documentaries of any period for they allow the imaginary to speak, which in the bad sense of documentary is forbidden.

TE: But, of course, in documentaries themselves, what really speaks is the imaginary.

EC: The stock footage of any period is meant to be a recording of reality but it is completely open to the imagination. For me there is a kind of displacement of roles, the fiction film becomes a document and the would-be document opens itself to the imaginary.

TE: Why do you think that the footage we have from the 30s and 40s is so seductive?

EC: I wonder if the reason I find the images so rich is that they seem to come from such a violent era.

TE: Both the war years and the pre-war period have undergone an extraordinary revival in all forms. Maybe because we also live in a world of public spectacle using roles, images, signs, self-display, and in many ways the 30s and 40s were a self displaying, narcisstic period on a massive scale but more naively so; perhaps the spectacle of those years holds an attraction because even aesthetically it anticipates our own, more guilty or more provocative narcissism.

EC: I wonder ... I did choose to make this film on negative and not just on video, as the I.N.A. (Institut National de l'Audiovisuel) people wanted ... On the one hand I desired to see the images as they were once seen a film screen in 35 mm black and white, but also because those were pre-TV days and audiences were less used to seeing images of daily life and current affairs, and so the public image worked much stronger than today. People are now saturated with images and however uncritical, are familiar with their operation, whereas in the 30s and 40s I think people would still say: "It's true, I've seen it on the screen". Everybody is aware now that images can be manipulated. Then images had a much stronger capacity to impress people's imagination. Also there was the fact that people had to leave home to go to the cinema, whereas TV is in the house, the space of daily life. I think this made looking at images akin to a religious experience – you went to the cinema like you went to church and communicated with another world. I think this experience has been lost from watching films on TV. People only go on special occasions or for particular films, whether it is the intellectual cinemagoer or the Star Wars watcher, it's no longer a weekly event, a ritual.

TE: I would say that the religious dimension is much stronger today. When a large audience goes to the cinema, it's the end of the world they want to watch. But perhaps there is, after all, a secret complicity between this desire and a writer's perspective, such as Jiinger's. Borges recently quoted Mallarmés "everything exists to take shape in a book", and added: a writer knows that whatever he does, he does for writing.

EC: I cannot think of the relationship between, to put it at its bluntest, Art and Life, if not as a vampiric one. The "committed" films about the Third World exploit the misery that gives them a reason for being and reassure their enlightened audiences in rich countries; when I want to allow people to really see the face of a prisoner about to die, my film feeds on his victimisation. And I know that being aware of this is not enough. Jünger was aware of it all and didn't raise his little finger ... So what? Stop caring? Stop writing and making films? Again – I don't know the answer, and those offered to me look banal or obsolete. And I know I can't stop caring, or writing, or making films. Or just putting questions.