The Museum and the Moving Image: A Marriage Made at the documenta?

One of the most significant phenomena in the world of contemporary sound-image media – seemingly far removed from the almost daily revolutions on the Internet, and yet intimately connected with them – is the extent to which the moving image has taken over/has been taken over by museums and gallery spaces. There are many – good and not so good – reasons for this dramatically increased visibility in the contemporary art scene of screen, projection, motion and sound. Some are internal to the development of modern art practice, if one accepts that, for many of today’s artists, a digital camera and a computer are as much primary tools of the trade as a paintbrush and canvas or wire and plaster-of-Paris were a hundred years ago. On the other hand, there are also reasons internal to the cinema for such a seemingly counter-intuitive rapprochement: not least the much-debated (i.e., as much lamented as it is ridiculed) “death of cinema”, whether attributed to television, the video-recorder, the end of European auteur cinema or to digitization and the Internet. Cynics (or are they merely realists?) may rightly conclude that the ongoing musealization of the cinema suits both parties: It adds cultural capital to cinematic heritage and redeems its lowly origins in popular entertainment, and it adds new audiences to the museum, where the projected image or video installation – the statistics prove it – retain the visitors’ attention a fraction longer than the white cube, with its framed paintings, free-standing sculptures or “found objects”.

On reflection, however, matters are not at all straightforward, when the moving image enters the museum. Different actor-agents, different power-relations and policy agendas, different competences, egos and sensibilities, different elements of the complex puzzle that is the contemporary art world and its commercial counterpart inevitably come into play. In short, from a historical point of view, the museum and the motion picture are antagonists, each with its own institutional pedigree, and during the past century, often fairly contemptuous of the other. Shifting from the institutional and the discursive to the aesthetic, the contrast is even sharper: however snugly the “black box” can be fit into the “white cube” with just a few mobile walls and lots of dark fabric, the museum is no cinema and the cinema no museum: first of all because of the different time economies and temporal vectors, which oblige the viewer in the museum to “sample” a film, and to assert his or her attention span, oscillating between concentration and distraction, against the relentless forward thrust and irreversibility of the moving image in the cinema, carrying the spectator along. But museum and movie theatre are also poles apart because they belong to distinct “public spheres”, with different constituencies, popular and elite, collective and individualized, for the moment (of the film’s duration) and for immortality (of the “eternal” work of art).

Given these incompatibilities and antagonisms, the forces that in the last three decades have brought the two together must have been quite powerful. The dilemma of contending public spheres having to come to terms with each other, for instance, can be observed quite vividly in the fate of (often politically committed) avant-garde filmmakers from the 1960s and 1970s. Since the 1980s, their films could no longer count on screenings either in art-et-essai cinemas, film clubs or even hope to find a niche on late-night television programs. As financing from television and state subsidies began to dry up, some found careers as teachers in art academies, and others welcomed a second life as installation artists, commissioned to create new work by curators of international art shows like Kassel’s documenta. Especially after Catherine David in 1997 invited filmmakers from France, Germany, Belgium and Britain to documenta X (among them Harun Farocki, Sally Potter, Chantal Akerman, Ulrike Ottinger as well as H.J. Syberberg and J.L. Godard), the cross-over has continued at the Venice Biennale, the Whitney Biennial, at Carnegie Mellon, the Tate Modern, Berlin, Madrid and many, many other venues. These filmmakers-turned-installation artists are now usually named along with artists-turned-filmmakers such as Bill Viola, Fischli & Weiss, Johan Grimonprez, William Kentridge, Matthew Barney, Tacita Dean, Pippilotti Rist, Douglas Gordon, Steve McQueen or Sam Taylor-Wood.

Without opening up an extended balance sheet of gain and loss arising from this other “death of (this time, avant-garde) cinema” and its resurrection as installation art, a few observations are perhaps in order. First, the historical avantgardes have always been antagonistic to the art world, while nevertheless crucially depending upon its institutional networks and support: “biting the hand that feeds you” is a time-honored motto. This is a constitutive contradiction that also informs the new alliance between the film avant-garde and the museum circuit, creating deadlocks around “original” and “copy”, “commodity” and “the market”, “critical opposition” and “the collector”: films as the epitome of “mechanical reproduction” now find themselves taken in charge by the institution dedicated to the cult(ure) of the unique object, whose status as original is both its aura and its capital. Second, as already indicated, several problematic – but also productive – tensions arise between the temporal extension of a filmwork in a gallery space (often several hours: Jean-Luc Godard’s 260-minute HISTOIRE(S) DU CINÉMA, Douglas Gordon’s 24 HOUR PSYCHO, Ulrike Ottinger’s 363-minute SOUTHEAST PASSAGE, Phil Collins’s 2-hour RETURN OF THE REAL), and the exhibition visitors’ own time-economy (rarely more than a few minutes in front of an installation). The mismatch creates its own aesthetics: for instance, how do I, as viewer when confronted with such overlong works, manage my anxiety of missing the key moment, and balance it against my sense of surfeit and saturation, as the minutes tick away and no end is in sight? Some of these extended works, in confronting viewers with their own temporality (and thus, mortality) are no doubt also a filmmaker’s way of actively “resisting” the quick glance and the rapid appropriation by the casual museum visitor: regret or a bad conscience on the part of the viewer being the artist’s sole consolation or revenge. Other time-based art, on the other hand, accommodates such random attention or impatient selectivity by relying on montage, juxtaposition and the rapid cut: artists have developed new forms of the collection and the compilation, of the sampler, the loop and other iterative or serial modes. In the film work of Matthias Müller, Christian Marclay or Martin Arnold, it is repetition and looping that takes over from linear, narrative or argumentative trajectories as the structuring principles of the moving image.

Returning to the institutional aspect: one of the most powerful forces at work in bringing museum and moving image into a new relation with each other is the programmatic reflexivity of the museum and the self-reference of the modern artwork. Entering a museum still means crossing a special kind of threshold, of seeing objects not only in their material specificity and physical presence, but also to understand this “thereness” as a special kind of statement, as both a question and a provocation. This “produced presence” of modernist art is both echoed and subverted by moving image installations, often in the form of new modes of performativity and self-display that tend to involve the body of the artist (extending the tradition of performance artists like Carolee Schneeman and Yvonne Rainer, as well as of video art quite generally), even to the point of self-injury (Marina Abramovic, Harun Farocki). Equally relevant is the fact that installations have given rise to ways of engaging the spectator other than those of either classical cinema or the traditional museum: for instance, the creation of soundscapes that convey their own kind of presence (from Jean Marie Straub/ Danielle Huillet’s synch-sound film-recitations to Janet Cardiff/George Bures Miller’s audio walks), or image juxtapositions/compositions that encourages the viewer to “close the gap” by providing his/her own “missing link” (Isaac Julien, Stan Douglas, Chantal Akerman) or make palpable an absence as presence (Christian Boltanski), each proposing modes of “relational aesthetics” (Nicolas Bourriaud) that are as much a challenge to contemplative, disinterested museum viewing as they counter or critique cinematic modes of spectatorship (voyeurism, immersion, as well as its opposite, Brechtian distanciation).

However, what the marriage between museum and moving image most tellingly puts into crisis is the relation between stillness and movement, two of the vectors that have always differentiated painting and photography from the cinema and sound. The museum space here is able to take key elements of the cinema – such as the face and the gesture, or action and affect – and articulate them across new kinds of tensions and (self-) contradictions, also conducting a more general interrogation of what constitutes an “image” and what its “viewer” (Bill Viola, Dan Graham, Christian Marclay, Chris Marker and many others).

Suspending Movement, Animating the Still

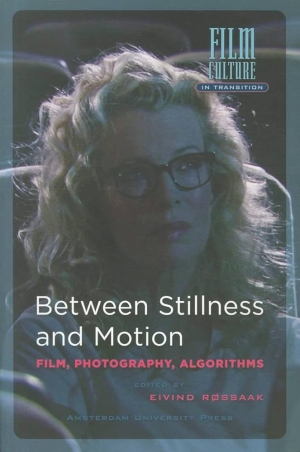

Before developing some of the consequences of the dividing line between still and moving image having become “blurred” – the blur being one of the concepts I shall touch upon in passing – it may be useful to look at how this “suspended animation” has been theorized and contextualized in a recent study, Eivind Røssaak’s The Still/Moving Image: Cinema and the Arts.1 Røssaak’s inquiry into the current state of the moving image situates itself strategically at the interface of several crossroads and turning points: the photographic/post-photographic/digital divide, but also the divide between “attraction” (or spectacle) and “narrative” (or linearity). It takes on board the dissensus between the commercial film industry and avant-garde filmmaking, just as it thematizes the institutional divide between screen practices in cinema theatres and screen practices in the museum space. To quote from the author’s programmatic introduction: “In recent decades there has been a widespread tendency in moving image practices to resort to techniques altering or slowing down the speed of motion. Creative uses of slow motion, single frame advances and still frame techniques proliferate within digital cinema, avant-garde cinema and moving image exhibitions. This project investigates this tendency through a focus on aspects of three works that are representative for the tendency, show different aspects of it and are widely influential: Andy and Larry Wachowski’s THE MATRIX (1999), Ken Jacobs’s TOM, TOM, THE PIPER’S SON (orig. 1969, re-released 2000), and Bill Viola’s THE PASSIONS (2000-2002).”2

As can be seen by the choice of works – all three situated both at the threshold of the new millennium and in different ways referring back to another moment in time, of which they conduct a form of archaeology – Røssaak raises a number of pertinent issues, while concentrating on “movement” and “immobility” as the key parameters. Aware of the self-conscious historicity of the works chosen, the author can focus on some aspects of the aesthetic regime put in crisis, without having to examine the full historical and critical ramifications, as briefly sketched above, when considering the moving image meeting the museum. “Immobility” thus becomes a shorthand or cipher, thanks to which different theoretical-aesthetic investigations into the nature and fate of “the cinematic” today can be deployed, while allowing the focus to firmly remain on these three specific, yet significantly distinct examples of filmic and artistic practice.

The strategic advantage of The Still/Moving Image for someone within film studies is that several of the key concepts are well established in the field and will be familiar to readers with an interest in cinema studies: “cinema of attraction”, “media archaeology”, “structuralist film”, “found footage” are terms with firm connotations gained over the past two decades. Other concepts are more vague or metaphorical (“spirituality”, “negotiation”, “excavation”, for instance). While this can lead to problems of coherence and consistency, with occasionally abrupt shifts in the levels of abstraction, the usefulness of the book lies above all in the judicious and felicitous choice of contrasting-complementary case studies, each of which is given a highly original historical placement and subjected to a complex and multi-layered historical hermeneutics. The theoretical framings, taken from art history (G.E. Lessing, Ernst Gombrich), new media theory (Lev Manovich, Mark Hansen) and film studies (Sergei Eisenstein, Raymond Bellour, Tom Gunning), are combined with empirical research (in archives, on site and in museums), which in turn lead to insightful observations on a wide range of works (from Mantegna to Franz Kline, from Tintoretto to Hogarth, from Hieronymus Bosch to Eadweard Muybridge), spanning five centuries and encompassing sculptures, altar pieces, paintings, etchings and chronophotography. Such a broad sweep does not only offer valuable context and historical background to the three works discussed in detail; it locates movement and motion in artworks across several moments of transition in the history of Western pictorial representation, thus contributing to the new discipline of “image-anthropology”, as championed, for instance, by Hans Belting and inspired by Aby Warburg.

The first chapter on THE MATRIX is, in one sense, typical of the thesis as a whole, in the way it homes in on a selected part of the work, but then offers an in-depth reading of the detail thus isolated. This, in the case of THE MATRIX is the so-called bullet-time effect, which occurs three times in the film, taking up no more than one minute of the film’s overall 136 minutes. On the other hand, this bullet-time effect in 1990, when the film came out, was the most talked about special effect since JURASSIC PARK’s dinosaurs, and quickly became a locus classicus among fans, “nerds”, and philosophers. Defined both by its extreme permutation of time (slow enough to show normally imperceptibly fast events) and space (thanks to the camera’s – and thus the spectator’s – point-of-view, able to move around a scene at normal speed while actions or people are shown in suspended animation or immobility), the bullet-time effect can be related back in its technique to Muybridge’s chronophotography, but in its effect of motion frozen in time, also to Andrea del Verrocchio’s statue of Colleoni on horseback. Linking CGI effects to both early cinema and Renaissance sculpture and thus to a long art-historical discourse about the representation of motion and time in the visual, photographic and plastic arts is a commendably illuminating contribution to several disciplines.

Equally full of surprises is the chapter on TOM TOM THE PIPER’S SON. Here, the many layers of correspondences and interrelations between the 1906 Billy Bitzer film and Ken Jacobs’ 1969-71 version are explored, all of them adding to the central discussion of movement and stillness. Røssaak shows that Jacobs’s repetitions, decelerations and “remediations” of this “found object” from early cinema – itself, as it turns out, a “remediation” or “re-animation” of a famous print from 1733, William Hogarth’s SOUTHWARK FAIR – keep doubling back into the very same problems already encountered by Hogarth (how to represent the asynchronous and yet collective movement of crowds) and Bitzer (how to isolate and thus “arrest” in both senses of the word, one of the participants – Tom who stole the pig – in the milling masses of spectators and players). Each of the three artists deals in his own way, and appropriate to his time and medium, with multiple planes of action, their consecutive phases, and the tensions between guiding but also refocusing the spectator’s gaze and attention. Even the modernist allusions in Jacobs’s work now make sense as part of the movement/ stasis/focus problem, which artists have posed themselves repeatedly over the centuries. But the references to abstract expressionism also afford an intriguing glimpse into the New York avant-garde scene of the 1960s and 1970s, with its intense cross-fertilization between artists, theorists and filmmakers. The brief section on copyright and the legal status of the moving image at the turn of the 20th century between “paper” and “photography” (the famous “paper print collection”) makes Bitzer’s original material and Jacobs’ rediscovery of it a particularly interesting case of the persistence of issues of ownership and common property when it comes to our image heritage and its preservation: all issues central to the museum’s role as potential guardian also of the cinema’s history.

The book’s key notion, “negotiating immobility” is, however, most aptly exemplified in the third chapter, which deals with Bill Viola’s installation THE PASSIONS, and particularly the piece called THE QUINTET OF THE ASTONISHED, a large rear-projected digital image of five people gradually and almost imperceptibly changing expression over a period of almost half an hour. Here, another formula from early cinema scholar Tom Gunning is put to good use: “the aesthetics of astonishment”. While Røssaak sees it mainly as a refinement and clarification of the better-known “cinema of attractions”, which due to its often indiscriminate application has now also come under attack, I think the term “astonishment” goes beyond the visual register of spectacle and “show”, as well as avoiding the problematic binary divides between “norm” and “deviancy” (especially when “cinema of attractions” is played out against “classical cinema” of “narrative integration”). More helpful, also for Røssaak’s case of how we perceive stillness and movement in relation to each other, seems to me the possibility that “astonishment” can identify what Gestalt-psychologist and others have referred to as “cognitive dissonance”, that is, a level of discrepancy, say, between eye and mind (as in: “the eye sees as real what the mind knows to be impossible”), or between the body and the senses (as in cases where the classic divide between mobile spectator/immobile view [museum] and immobile spectator/mobile image [cinema] is subtly displaced and rearticulated, which happens when the moving image enters the museum). Bill Viola himself suggests as much when he talks about the high-speed photography of THE PASSIONS’ continuous, if complexly choreographed movement, replayed and dilated by extreme slow motion as “giving the mind the space to catch up with the eye”. Røssaak handles an extremely suggestive analytical tool in this chapter, which conveys very well one of the key techniques of Viola (besides his own version of the bullet-time effect) for producing both cognitive dissonance and motor-sensory imbalance: namely that of the “desynchronized gazes” among the five figures, which create the oxymoronic sensation of a cubist temporality. As spectators, we do not know whether to stand stock-still in front of the projected image or mimetically mirror the slow motion of the bodies, thus finding ourselves, precisely, caught in “negotiating immobility”, i.e., trying to adjust to a “different” motion of “life” – or if you like, experiencing “ecological time” – in the midst of our hectic lives, dominated by timetables and the tick-tock of mechanical clocks.

Towards a Politics of Slow?

What is more natural than Røssaak ending his book with a gentle plea for “the politics of slow”: a worthy sentiment, no doubt, but hopefully also not just intended as a “reaction” to the generalized speed and acceleration of modern life. We do not want to make the museum merely a refuge, and art a compensatory practice. Especially if it is a question of “politics”, we need to see the “critical” dimension in movement itself – process, becoming, the possibility of transformation – lest immobility comes to signify not the absence or suspension of movement, but its arrest, with all the connotations of politics, policing and power this implies: “freeze” is, after all, what the cops say to a suspect in Hollywood movies. And one thing that the cinema is definitely not, in the world of the fine arts is a “suspect”, and one role the museum should not play is that of the cop (from THE MATRIX), “freezing” the cinema, either in time or in history, the way he unsuccessfully challenges Trinity, the film’s Protean heroine. “Negotiating immobility” must not become either a euphemism for the museum as mausoleum, or a code word for resistance to change.

And yet, resistance has been the mark of art for much of the 20th century, including that of cinema. In the contest of motion and stillness, however, what is “the dominant”, to which the artist is compelled to offer dissent? Is it the stasis of the photograph, overcome by the cinematic image that brings life and animation, or is it quick editing and the montage of fragments, with its overpowering rhetoric of agitation and propaganda, demanding of the artist to counter it with images that absorb and focus, rather than mimic the frenzied onrush of a speeding train, as in Dziga Vertov’s MAN WITH A MOVIE CAMERA? If speed was once perceived as the mark of modernity in the 1910s by Marinetti and the Futurists, or hailed by the Russian avant-garde of the 1920s as thrilling to the promise of technology and the impatient rhythm of machines, then the destructive energies unleashed by “lightning wars”, supersonic aircraft or rocket- propelled missiles have also reversed the perspective: just as “progress” is no longer the only vector taking us into the future, so speed may not be the only form of motion to get us from A to B. The modernist paradox seems inescapable: we are obsessed with speed, not least because we are fearful of change, a fear of the relentlessly inevitable which we try to make our own – appropriate, anticipate and inflect with our agency – through speed. In the cinema, a static high-velocity vehicle par excellence, we seek out that which moves us, transports us, seduces and abducts us, propels and projects us, while keeping us pinned to our seats and perfectly “in place”. Paul Virilio has expressed it most breathlessly, in his “aesthetic of disappearance”: Velocity, understood as space or distance, mapped against time or duration, reaches its absolute limit in the speed of light, where space and time “collapse”, i.e., become mere variables of each other. Is the cinema, as an art of light, asks Virilio, not always at the limits of both time and space, at the threshold of “disappearance”, whose negative energy is stillness? Gilles Deleuze’s opposition of the movement image and the time image intimates, among other things, not only a break in the relation of the body to its own perception of motion in time and space, but also a moment of resistance, a reorientation, where perception neither leads to action nor implies its opposite, while stillness does not contradict motion.

These “dromoscopic” considerations are to be distinguished from what has been called “the aesthetics of slow”, indicative of a kind of cinema that has reformulated the old opposition between avant-garde cinema and mainstream narrative cinema around (the absence of) speed. Possibly taking its cue from David Bordwell’s characterization of contemporary Hollywood, the “cinema of slow” sees itself as a reaction to “accelerated continuity”, where slowness – however expressed or represented – becomes an act of organized resistance: just as “slow food” is a reaction to both the convenience and uniformity of fast food, appealing to locally grown ingredients, traditional modes of manufacture and community values. No longer along the lines of “art versus commerce”, or “realism versus illusionism”, slow cinema (also sometimes referred to as “contemplative cinema”) counters the blockbuster’s over-investment in physical action, spectacle and violence with long takes, quiet observation, an attention to detail, to inner stirrings rather than to outward restlessness, highlighting the deliberate or hesitant gesture, rather than the protagonist’s drive or determination – reminding one, however remotely, of the “go-slow” of industrial protest, but also the “organic” pace of the vegetal realm.

Yet “slow cinema” can also be seen as a way of already thinking the musealization of the cinema into the contemporary practice of cinema, making the classic space of cinema – the movie theatre – into a kind of museum (of the Seventh Art), understood (in the counter-current that not only preserves the anti-cinema of the avant-garde, but also the “cinema of disclosure” of Europe’s post-war new waves) as the site of contemplation and concentration. The aural silentio of the museum’s ambient galleries, conveyed in measured pace and the stillness of the image, would return us to an inner-space that is both womb and refuge, both protest against and a retreat from a world, increasingly experienced as spinning out of control.

Different Ways of Thinking of the Moving Image

We are thus faced with two conceptions of the moving image in light of its century-old history. If we consider the classical view, arguing from the basis of the technical apparatus, there is no such thing as the moving image, neither in photographic, celluloid-based moving images nor in post-photographic video or digital images. In photographic film each static image is replaced by another, the act of replacement being hidden from the eye by the shutter mechanism in the projector; in the analogue video image and the digital image, each part of the image is continually replaced either by means of a beam of light scanning the lines of the cathode ray tube, or refreshed by algorithms that continually rearrange the relevant pixels. Motion is in the eye of the beholder, which is why cinema has so often seen itself accused of being a mere “illusion”, an ideological fiction, only made possible by the fallibility of the human eye: regardless of whether this “failure” was compensated by “persistence of vision” or the “phi-effect”.

The other view could be called Heraclitean. Given that “everything moves” and that change and thus motion, whether perceptible to the human eye or not, is the very condition of life (animal, vegetal and even mineral) at the macroscale as well as micro-level, the cinema (as moving image) is not an illusion, simulation or imitation of life but its approximation, by other (mechanical, mathematical) means. Henri Bergson is the much-quoted philosophical guarantor of such a view, at least as understood and interpreted by Gilles Deleuze. For Bergson, there is always priority of movement over the thing that moves, embedded as it is in duration, which, however, no image can represent. In Creative Evolution, Bergson even criticizes the cinema for passing static images off as movement, but Deleuze – with Bergson contra Bergson – argues that an image is always “in motion”, not merely because the eye restlessly scans, probes and touches even the (still) image in the very “act of seeing”: the still image is a “stilled” image, slowed down to the point of imperceptible motion, or stilled because it is taken out of the flow or extracted from it, but carrying with it as its virtuality the signs and traces of the movement to which it owes consistency, energy and substance.

While Deleuze’s Bergsonism is part of his overall philosophy of “multiplicity” and “becoming”, with roots in Spinoza and Nietzsche, his “revolution” in the way we can think about images in general and the cinematic image in particular is well suited for the recasting of the relation between stillness and movement also in the digital age. Before the advent of the digital image, photography and the cinema were traditionally seen as each other’s “nemesis”: each could speak to a particular truth, repressed or hidden in the other: the cinema – based as it initially was on the chrono-photograph – made us aware of the temporality enclosed or encased in the still image, which the cinema could liberate and reanimate, as it did in the very early performances of the Lumière Brothers, whose films habitually started with a projected photograph, suddenly springing to life. Conversely, photography has always been the cinema’s memento mori: reminding us that at the heart of the cinema are acts of intervention in the living tissue of time, that the cinema is “death at work”, in the famous phrase of Jean Cocteau. Film theory in the 1970s even went a step further: since cinema, in the very act of projecting moving images, represses the materiality of the individual frames that make up the celluloid strip, its “apparatus” cannot but be an instrument of power, at the service of an “idealist” ideology.

In art history, the 1970s also saw a revaluation, if not the incorporation, of photography into the canon of Western art. Photography’s ability to hold a moment in time and freeze in it not just a past, but to sustain a “future perfect” has been the source of its peculiar fascination to art historians, taking their cue from Walter Benjamin, Susan Sontag and especially Roland Barthes, whose insistence on the “tense” of the photograph is nonetheless unthinkable without the cultural experience of cinema against which it formulates a silent protest. Cinema is thus also the “repressed” of photography in the 20th century, at least in its intellectual-institutional discourse. As David Campany put it:

Still photography – cinema’s ghostly parent – was eclipsed by the medium of film, but also set free. The rise of cinema obliged photography to make a virtue of its own stillness. Film, on the other hand, envied the simplicity, the lightness, and the precision of photography.… In response to the rise of popular cinema, Henri Cartier-Bresson exalted the “decisive moment” of the still photograph. In the 1950s, reportage photography began to explore the possibility of snatching filmic fragments. Since the 1960s, conceptual and post-conceptual artists have explored the narrative enigmas of the found film still.3

As Campany goes on to point out, filmmakers in the ????s like Andy Warhol, Michael Snow and Stan Brakhage “took cinema into direct dialogue with the stillness of the photographic image”.4

Working on the Moment: Stillness in Motion and Motion within Stillness

These dialogical-dialectical relations between photography and cinema may well have come into another crisis with the effective disappearance, in the digital image, of either material or ontological difference between still and moving image. Instead, attention is gradually being refocused on the aesthetic possibilities that arise within digital imaging for the degrees, the modulations and modalities of stillness, arrest and movement, such as suggested earlier around the “bullet time” effect in THE MATRIX, but now in the realm of the fine arts. As Chris Dercon, commenting on the work of Jeff Wall, has remarked:

The moving image has liberated exhibition spaces from the illusion of the static world. Things we generally associate with the visual arts suddenly start to move on a large scale. Or should we say that suddenly we have become aware that there are static images? As a result of the new applications of photography, cinema and video, we can now really reflect in our museums on what stillness is. From Jeff Wall’s point of view, the stillness of still pictures has become very different, otherwise one couldn’t explain the current fascination with still photography.5

In consequence, just as digital photography can now produce the “photographic mode” as one of its options or effects, so the aesthetics of both photography and cinema have to be re-thought in terms of particular historical “imaginaries”, rather than being defined by specific properties inherent in each medium, least of all the criteria of stillness and movement. Such an idea of photography and cinema as merely different applications or culturally coded uses of a new (or rather, age-old) mode, namely that of the graphic image (including the photographic image), of which the digital image would merely be the latest installment, as it were, no doubt challenges our concepts of the photographic and the cinematic in all manner of ways. For example, it places the relationship between movement and its suspension into a temporal frame that belongs more to the spectator rather than to the object. Cartier-Bresson’s “decisive moment” that needs to be “captured” before it disappears “out there” and “forever” is turned against its own metaphysics of time (i.e., the manifest palpability of time we call the moment), when compared to Jeff Wall’s photographic light boxes or the video portraits of Gillian Wearing, where an elaborate staging of the “instant” or the “moment” (whether taken from a Hokusai woodblock print, a London mews, or a sunlit afternoon street in Los Angeles) produces and post-produces time (i.e., the temporal attention and extension the viewer gives to the work). It comes to constitute the artist’s work on the moment rather than registering the moment’s work on the artist.

A quite different example of such “work on the moment” occurs in CHUNGKING EXPRESS (1994), directed by Wong Kar Wai, who, together with his cameraman Christopher Doyle, might be said to realize a “photographic imaginary” but using cinematic means: not by inserting stills into his film, freezing the frame, or composing his films of photographs, as one finds them in the films of the Nouvelle Vague, from Jean-Luc Godard (A BOUT DE SOUFFLE) to François Truffaut (LES QUATRE CENT COUPS) and Chris Marker (LA JETÉE). I am also not thinking of the scenes in CHUNGKING EXPRESS that feature “stains” of motion blur in an otherwise sharp image – though these shots deserve more comment, not least because they play another variation on our theme, insofar as the blur records objects and people still in motion when the image has already been fixed. As the trace of a movement that exceeds another movement, the motion blur in the photographic-cinematic mode was often regarded as either a technical flaw or an index of a special kind of authenticity. The sharp image, from which any trace of motion (and thus its temporal index) is banished, came to be the paradigm of normative representation. From the vantage point of the “digital”, on the other hand, the blur can realize a “layering” of degrees of stillness and motion repressed or deemed unacceptable in the photographic (or the cinematic), while nonetheless embedded as a possibility and an absent presence in the very opposition of stillness and motion.

However, I have in mind another scene: in order to convey the co-presence and overlap of two temporalities – one iterative and in the modality of “duration”, the other focused on the moment; one external and impersonal, the other subjectively inflected with anticipation and boredom – Doyle shot a scene of passersby in a busy shopping street, while inside a bar, one of the protagonists, Cop 633, sits drinking coffee, with the amateur stalker Faye gazing at him in rapt absorption. What we see, however, is the non-encounter between the man and the woman taking place in a drifting, slow-motion dreamy haze of unrequited longing, while the people outside speed past these ghosts, lost to desire and ennui – a powerful metaphor for the life that escapes them, as they seek ways to live it more intensely, in a city that never rests. It is the sort of slowing down of movement we associate with Bill Viola, but instead of being “done digitally”, Doyle shot the scene with an analogue camera, asking the actors to go into slow-mo mode, as if in a Kung Fu movie, while filming the crowds at normal speed – except that there is nothing “normal” about a scene so effectively combining two different “sheets of time” in the single image: time stands still for some, while it rushes past for others. Realizing an effect now considered typical of the “digital”, and doing so with the resources of the cinema, Wong Kar Wai and Doyle anticipate one of the changes that the digital was to bring to the parameters of motion. Demonstrating a different kind of materiality and malleability of time in the image, they also implicitly confirm that we should not attach these changes to digital technology per se. Such scenes herald a new aesthetic of duration beyond movement and stillness, arising from both film and photography, but perhaps to be realized by neither.

Having become a “way of seeing” as well as a “way of being”, the cinema has made itself heir to photography, one might say, not by absorbing the latter’s capacity for realism, or by turning the still image’s irrecoverable pastness into the eternal present of the filmic now. Rather, by handing its own photographic past over to the digital, it might fulfill another promise of cinema, without thereby betraying photography. The particular consistency of the digital image, having less to do with the optics of transparency and projection and more with the materiality of clay or putty, carries with it the photographic legacy of imprint and trace, which as André Bazin saw it, is as much akin to a mask or a mould as it is a representation and a likeness. Bazin’s definition of the cinema as “change mummified” may have to be enlarged and opened up: extended to the digital image, it would encompass the double legacy of stillness and movement, now formulated neither as an opposition in relation to motion, nor as a competition between two related media, but in the form of a paradox with profoundly ethical as well as aesthetic implications: the digital image fixes the instant and embalms change: but it also gives to that which passes, to the ephemeral, to the detail and the overlooked not just the instant of its visibility, but the dignity of its duration.

Here, then, lies the task for the museum, as it comes to terms with time-based art increasingly supplementing if not substituting for the lens-based art of the last century. With photographs now digital and intuitively understood as segments stilled from the flow of time, both film and photography, whether digitally produced or merely digitally understood, are an archive not only of moments, epiphanies and illuminations, or actions in the mode of the movement, cause and consequence, but also of sensations, affects and feelings that are experienced as transitory, inconsequential and ephemeral. Hence the ethical task of their sustainability, ensuring that they endure: in memory, as intensities, as the shape of a thought, even as their perception exceeds the eye and encompasses the whole body as perceptual surface. This “duration of the ephemeral” would not be in the service of slowing down the pace of life, nor an act of resistance against the tyranny of time, but would grant to the fleeting moment its transience as transience, beyond stillness and motion, beyond absence and presence.

Notes

Eivind Røssaak, The Still/Moving Image: Cinema and the Arts (Lambert Academic Publishing, 2010) is a revised edition of Negotiating Immobility: The Moving Image and the Arts (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Oslo 2008).

Quoted from the blurb of Røssaak’s dissertation (Negotiating Immobility: The Moving Image and the Arts, 2008).

David Campany (ed.), The Cinematic (Documents of Contemporary Art), Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007, ‘Introduction’ p. 1.

Ibid., p. 11.

Chris Dercon, ‘Gleaning the Future from the Gallery Floor’, Vertigo vol. 2, no. 2, spring 2002, online at: http://www.vertigomagazine.co.uk/showarticle.php?sel=- bac&siz=1&id=574 (last accessed September 30, 2010).