Introduction

This month sees the move of the European Central Bank into its new headquarters in Frankfurt/Main, after a building period of six years and ten years of controversies over its siting, over the design that eventually won the tender, cost overrun from 680 million to 1.3 billion, as well as a legal case over the damage inflicted on a listed building integral to the site. These bones of contention do not include the Euro-Crisis of 2008/9, the halt to the expansion of the Euro-zone, and continuing doubts over the viability of the single currency for the participating EU members. The extent of lingering discontent around the building project can be gauged from the fact that the ECB has not announced an official opening date, or confirmed whether there will be an opening ceremony, aware of previous protests organized by a group of activists calling themselves the “Blockupiers” and threatening to disrupt any planned event.

Nonetheless (or because of these factors), this is a useful occasion to put the opening of this modern super-building into several historical contexts. One such context is the importance of Frankfurt in the history of modern architecture and in particular, of its famed social housing projects from the 1920s. Another context is the increasing importance of landmark or signature buildings – preferably designed by a “starchitect” – for the identity of contemporary cities, and by implication, such a building’s role in branding public space, irrespective of whether the brand is the city itself (think Bilbao), a museum franchise (think Guggenheim, the Paris Louvre in Abu Dhabi), an entertainment corporation (the Walt Disney Concert Hall in LA) a multinational automotive company (BMW World in Munich), a transnational institution such as the ECB, or a political idea, as is now claimed for the ECB design: “The building is a three-dimensional statement for Europe,” according to the architect Wolf Prix of Coop Himmelbau. And: “The battle around a shared currency now has a new address: the twin towers of the ECB in East Frankfurt. The architecture is like an exclamation mark. It makes the building so spectacular but also so political. If the European Union has lacked anything so far, it was this: a clearly visible sign. Now this sign is standing directly on the Main River, 202 meters high.” This passage is from a recent article in the Süddeutsche Zeitung, a leading national newspaper. The same message is put across by the promotional video the ECB uploaded last week.

Rather than discuss one of the core controversies, hinted at in the video, namely the partial destruction of a historically unique listed building, what I want to propose is to use the arrival of the ECB building in Frankfurt, and the history of what is now reduced to its lowly plinth and entrance hall, the once giant Central Market for a small perspective correction on Frankfurt as a key architectural and cultural location of the 20th century, by bringing into the debate another Frankfurt landmark building, also the headquarters of an international corporation, and also historically controversial and contested to this day, namely the IG Farben building. Such a comparison suggests a number of pertinent parallels between the 1920s and now, while also pointing to a constellation of political agents, business interests and avant-garde actors that brings into view not only competing strategies for the modern city, but also different visions of a united Europe.

Das Neue Bauen

The City of Frankfurt is known for many things: it is the birthplace of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Germany’s greatest poet, of Mayer Rothschild, the “founder of international finance”, as well as the (premature) birthplace of German Democracy: the Frankfurt Parliament of 1948. In the 20th century, it has given its name to The Frankfurt School (The Institute for Social Research founded in 1923 by Max Horkheimer and Felix Weill, with T.W. Adorno as its most prominent member and to Das Neue Frankfurt (1925–X) synonymous with Modernism in architecture and urban housing, whose leading figure was Ernst May, but whose best-remembered product is the Frankfurt Kitchen. After 1945, Frankfurt was the seat of the US Army’s High Command in Germany, which occupied the landmark building I just referred to, and made its Headquarters from 1945 until 1994. As Germany’s only city with skyscrapers, Frankfurt came to be known as Mainhattan and today it is, next to London, the financial hub in Europe, which is why the EU decided to locate there its European Central Bank.

When singling out Das Neue Frankfurt, I have to briefly sketch a larger context – that of Das Neue Bauen, which in the history of modern architecture occupies a special place, as the German variant of the ‘International Style’.1 Mies van der Rohe, Walter Gropius, Erich Mendelsohn, Martin Wagner and Ernst May are considered to be its leading theoreticians, practitioners and propagandists. Besides Berlin and Dessau (seat of the original Bauhaus), it was above all the city of Frankfurt, which in the years 1925–1930 became famous throughout Europe, not least because its architects and planners promoted a new domestic environment, centred in part on the needs of the working class and in part on the emancipatory aspirations of women.

The socio-historical background and political platform supporting Das Neue Bauen in Germany was the general housing crisis in the immediate post-WWI years, which in Germany’s manufacturing centres reached desperate proportions by 1923–24.2 With the pre-war build up of massive industrialization, the working classes (recently migrated from the countryside into the cities as the new proletarian labour force for the factories) were often very poorly housed, for which the notoriety of the Berlin tenement blocks (so-called Mietskasernen) only provides an inadequate picture. Infant mortality, communicable diseases and domestic violence had taken on epidemic proportions, aggravated by a disastrous outbreak of the Spanish flu and widespread famine during the winter 1919/20 (the Rübenwinter). The four years of the war from 1914–1918 had seen no domestic building projects whatsoever, yet because of war-reparations, inflation and a breakdown of the tax system, there was, in the first post-war years, also little money to start new public housing schemes. Next to nothing was undertaken until the stabilization of the currency and the recovery period, starting in 1924/25, when a boost to housing became financially possible thanks to the Hauszinssteuer (house interest-rate tax), a tax initially suggested by the Berlin city planner Martin Wagner, and levied on house owners, to be used for social housing projects, which compensated society for the fact that mortgages had effectively been reduced to zero thanks to hyper-inflation, while the value of property had remained stable or had increased.3 There followed a brief period of rapid economic expansion from 1925 until the Wall Street Crash in 1929, which hit Germany hard around 1930/31, with unemployment rising in 1932 from four-and-a-half million to six million within a matter of months. As is well known, this crisis created the political conditions and the social unrest that led to the seizure of power by Hitler and the Nazis, March 1933.

It is this brief golden age preceding the Crash that defines the life of Das Neue Bauen. A period of just some five years managed to shape architecture, city planning and the idea of urban space so decisively that it set the agenda for the international discussion on housing and urbanisation until well into the 1970s. In neighbouring countries less affected by the war, notably Austria (Vienna), Switzerland (Zurich, Basle) and The Netherlands (Rotterdam and Amsterdam), social housing initiatives were actually a little ahead of Germany, and it is characteristic that nationals from these countries, Grete Schütte-Lihotsky (Vienna), Hannes Mayer (Basle) and Mart Stam (Rotterdam) should play an important role in Frankfurt’s developments.

Das Neue Frankfurt

The driving force behind the Frankfurt housing initiative was Ernst May Frankfurt-born architect, initially active in Breslau (now: Wroclaw), whom the newly elected mayor of Frankfurt, the liberal-democrat Ludwig Landmann recalled to his home city in 1925 and put in charge of urban planning and to head the housing department. May had been educated in England, studying with Raymond Unwin, one of the inventors of the concept of the garden city. As an architect, May was a convinced modernist of the cube (whitewashed walls, small ribbon windows towards the street and large picture windows towards the garden, topped by a flat roof.

Politically, May was probably further to the left than Landmann and his liberal-social democrat coalition. However, it is most unlikely that he had ever joined the Communist Party, even though his design team was known as the May Brigade and by the right-wing press he was vilified as a cultural Bolshevik (Kulturbolschewist). In 1930 May left Frankfurt, with the majority of his planning staff, on the invitation of the Soviet Government, for whom he and his brigade designed the industrial city of Magnitogorsk. Soon disenchanted by the working conditions and the chicaneries of the Soviet planning bureaucracy, May left Moscow in 1934. He found work by semi-exiling himself to Tanzania, then German West Africa, where he spent the war before returning to (West) Germany in 1945, to head various urban reconstruction schemes mostly in Hamburg.

In his plans and housing ideas for Frankfurt, May was responding to the showcase Weissenhofsiedlung in Stuttgart, as well as to Le Corbusier’s vision of the new city, La Ville radieuse, countering it with a less top-down and more pragmatic socialist housing programme, which he called ‘die Wohnung für das Existenzminimum’ (housing for subsistence-income families), a topic on which May organized an international conference in 1927, sponsored by the CIAM – the International Congress of Modern Architects – whose second world congress this was.

Thanks to May’s efforts, Das Neue Frankfurt (DNF) soon became a recognized name for design innovations, city planning and energetic public works schemes, doing his best to win acceptance in Frankfurt for the then still very controversial modular system of housing construction. His activities besides city planning extended well beyond conferences. Under the label DNF he and his collaborators published a glossy journal (das neue frankfurt), organized trade fairs, edited The Frankfurt Register, a catalogue of furniture & accessories, gave and invited public lectures, did radio broadcasts and even had a regular film club, with screenings of avant-garde works and visits by celebrities such as Joris Ivens, Dziga Vertov or Rudolf Arnheim. May’s ability to extract maximum publicity from his Frankfurt ventures gave him an exceptional status within Europe, in some ways disproportionate to the actual achievements. In Frankfurt itself he faced opposition throughout his tenure, which came to a head after he had left. One such attack in a pamphlet from late 1931 read: “The agitator behind these strident endeavours was the Municipal Master Builder May, who for years pushed through his revolutionary system by any propaganda means available, using newspaper articles, lectures and the help of extremely expensive photo advertising. […] The specially founded Frankfurt magazine […], had the [sole] task of spreading May’s ideas like a mass contagion […].”4

I now want to give this story a different slant by first extricating it somewhat from the self-promotional efforts of Ernst May, in order to introduce a figure I consider at least as central, namely the already mentioned Mayor of Frankfurt, Ludwig Landmann; and second, I want to put the narrative of the Frankfurt housing settlements into a broader perspective, where the mass housing initiative can be seen as only one part of a more encompassing and as it were, more organic and holistic vision for Frankfurt Modern. One of the reasons why the settlements gained such prominence was that many of the other elements of the larger concept were either never realized, due to the consequences of the Crash of 1927, or they were perceived in isolation, rather than as integral elements of a Master Plan. I therefore propose a sort of virtual or counterfactual history of Frankfurt Modern, which includes these other dimensions, reconstructed across documents only recently recovered, or rather, documents come to new attention thanks to events that have made these hitherto buried aspects once more topical – such as the Euro-crisis following the 2008 Crash, and the attention given to the ECB’s building plans, which as indicated, incorporated (or swallowed) one of the key buildings that formed part of this other vision of Frankfurt: the Central Market.

I’m calling it Frankfurt Modern, but might also have labelled it “Das Alte Frankfurt” (the old Frankfurt), partly because it involves the old Frankfurt bourgeoisie, along with big business, industry and the financial sector, and partly because it highlights how architectural Modernism and political Conservatism may not necessarily be polar opposites, and how an intriguingly dual perspective of a united Europe connects the Frankfurt of the 1920s to the Frankfurt of the 2010s. Rather than a “counterfactual history”, then, what I’m proposing is an “augmented reality” history, in which the virtual “if-only” aspects exist side by side or overlap with the historical record, as we know it from the textbooks of German Modernism. Considering how the virtualization of public space has become a well-aired topic in urbanist literature and architectural debates, most recently under the title “Brand-driven City Building”, the Frankfurt Modern case study should be understood as part of an archaeology of this “spatial engagement of capitalism” seeking to “create media-rich […] realities”. Yet I could also enlist as my witness a critic and theorist from the 1920s, namely Siegfried Kracauer, himself a trained architect and a keen observer of urban modernism, who in his collection of essays, tellingly titled “Frankfurter Turmhäuser” (Frankfurt Highrises) already responded to some of these transformations of the city-scape under the impact of a new visual culture.

Frankfurt Modern: Ludwig Landmann

In other words, with Frankfurt Modern I want to outline the cultural topography of a city, that does not present a linear history of a hundred years of Frankfurt urbanism, or offer a narrative alternating between the breaks and continuities (so typical of German history in the 20th century). Rather, I am sketching a certain constellation from the early part of the 20th century around an ambitious plan to create a Greater Frankfurt at the heart of Europe, by a combination of landmark buildings, social housing projects, a modern transport infrastructure of rail, road, air and water, as well as the use of the technical media of sound and vision. Across these points of reference, the city emerges as a living being or organism, making special provisions for health (sports facilities and clinics), education (schools, university), nutrition (Central Market, allotment gardens), recreation (public parks, exhibition grounds) and the arts (music festivals, an art academy). By focusing on a number of emblematic buildings and charismatic individuals, one can retrace across the idea of Greater Frankfurt also two versions of Europe – a Europe of the corporate elites, and a Europe of “sustainable existence” – each using “culture” (rather than party politics) as their battleground. These competing visions have surprising echoes in the present, especially in Germany, where the green movement, sustainability and the environment have put down political and cultural roots like nowhere else in Europe.

Frankfurt had always been a hub for trade and finance, and it had developed a strong civil society during the 18th century. Home to Germany’s largest Jewish population, it was known for its radical politics ever since the French Revolution. With close ties to France – it was occupied by the French under Napoleon – and as host to the already mentioned provisional German parliament in 1848, it became one of the targets of Prussia’s Western expansion during the Franco-Prussian War and in 1866 Prussian troops marched into Frankfurt, which subsequently became part of Prussia and had to pay substantial reparations. In a very Roman gesture, Karl Fellner, the last mayor of the free city, committed suicide.

What has made Frankfurt strategically special is its geographical position, close to the confluence of two rivers – the Rhine and the Main – as well as its equidistance from important German and European cities: it links Hamburg and Basel, Paris and Berlin, Amsterdam and Munich. In the 20th century it became an attractive location for various industries – the Adler automobile and typewriter company, a fledgling aircraft industry, AEG Electrics, the Hoechst chemical works, leather goods, as well as banking and publishing. To this day, Frankfurt rivals Berlin, Leipzig and Hamburg as the heart of German book publishing: the Frankfurt book fair goes back to the days of Johann Gutenberg, who invented printing in neighbouring Mainz, and since 1949 the Frankfurt book fair has established itself as the world’s largest.

It is therefore not surprising that the master plan for Frankfurt that began to take shape in the early years of the 20th century should give a high priority to culture and the arts, its basically “democratic-republican” outlook favouring civic institutions to provide patronage and sponsorship, thereby setting itself off from the so-called Residenzstädte like Weimar, Potsdam, Stuttgart, or Munich which throughout the 18th & 19th century had enjoyed feudal patronage from their local princes or kings. But it took the shock of the WWI and the ensuing misery experienced by the urban masses to galvanize Frankfurt’s municipality into action. It must not be forgotten how the post-WWI inflation period (still invoked to this day as the reason why Germany is so austerity prone and obsessed with fiscal rectitude when it comes to keeping a stable currency), how the inflation period from June 1921 to January 1924 not only bankrupted large sections of the middle class, but also wiped out endowments, bequests, inheritances and other funds that had supported art institutions like museums, libraries, orchestras or opera houses (here, too, echoes of more recent endowment crises).

While previous mayors – notably Johannes von Miquel (mayor from 1880–1890) and Franz Adickes (mayor from 1890–1912 – had been promoting Frankfurt as a modern city with large infrastructure projects, such as ring roads, the expansion of the Main harbour and a palm garden, it was the election of Ludwig Landmann in 1924 that changed the fortunes of Frankfurt and raised its ambitions from being a regional centre to becoming a European metropolis.

Already before he became Mayor, Landmann published a sort of manifesto in the Frankfurter Zeitung where he argued that “the integration of the Rhein-Main area into a large, single and viable organism will happen one day because it must happen.” In other words, building on the momentum generated by his predecessors, Landmann, once elected, ordered the Wirtschaftsamt (the economic planning office) to publish a glossy brochure that envisioned Greater Frankfurt not only as the centre of the region, but assigned to it an important national and international role within an increasingly integrated Europe, meaning Germany, France and Italy. The brochure mapped out a Rhein-Main corona of cities with Frankfurt at its centre, but with arms or tentacles reaching well beyond.

Specifically, the Landmann master plan entailed four main components:

(1) bring, if necessary by fiat, some of the surrounding communities, villages and small autonomous cities within the jurisdiction of Frankfurt, thus extending the physical size of the city, in order to broaden its tax basis as well as gaining agrarian land for much needed housing developments. This proved to be quite controversial and was much resisted, not least by these communities.

(2) maximize the natural geopolitical advantages of Frankfurt by funding extensive improvements in transport and mobility: making Frankfurt the hub of rail transport, building an airport, further enlarging the river’s navigability, and promoting a trans-German road system that connected Frankfurt to Hamburg and Basel. Landmann was instrumental in founding the Ha-Fra-Ba Alliance (“Interessengemeinschaft”), which is considered the precursor of the German Autobahn system.

(3) attract major national firms to establish their headquarters in Frankfurt, in order to create jobs and to provide for this workforce an improved quality of life.

(4) make Frankfurt energy-independent by acquiring rights to coal fields in the region and securing long-term delivery contracts (think Russia and the EU today).

Landmann’s importance for Frankfurt is generally recognized. A recent entry, for instance, credits him with “laying the foundations for the economic recovery of Frankfurt in the 1920s, with plans which only came to full fruition after 1945. Best known are his infrastructural measures, among them the Waldstadion (Forest Stadium), the Central Market and the Airport Frankfurt-Rebstock.”

Landmann’s Landmarks

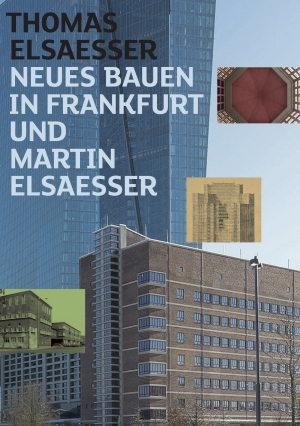

What is less known is that next to the housing developments of Römerstadt, Praunheim, Westhausen, Höhenblick etc., Landmann also commissioned a series of representative landmark buildings for the city centre and along the Main River, that were to symbolize Frankfurt’s civic pride, while also directly contributing to the holistic vision he had of a city able to provide for the bodily needs, cultural aspirations and spiritual wants of its population. These landmark buildings included the Central Market, a new City Hall, a new University Library that also served as the city’s public library, an Art Academy, a modern indoor and open-air swimming pool by the Main River, a modern hospital and clinic for mental disorders, and an extension to the popular Palm Garden Society House, used for receptions, weddings, conferences and civic functions. Of these projects, only three could be realized in the short period between 1925 and the downturn of 1930: the Central Market, the Clinic and the Palm Garden House extension. All the others remained on the drawing board. These landmark buildings were the responsibility of another senior architect, brought to Frankfurt at the same time as Ernst May in 1925, and while nominally answerable to May, headed his own office and staff as the Artistic director of City Planning. His name was Martin Elsaesser, mentioned in the ECB video as the architect of the said Frankfurt Central Market, but the author of all the designs I just showed, as well as the architect of the Clinic for Nervous Disorders and the Palm Garden House extension, along with a dozen other buildings. Elsaesser came to Frankfurt from Cologne, where he had been director of the Cologne Art Academy, for which he designed not only a new building, but also redesigned the curriculum. Evidently, he did not have the same skills as May in promoting his vision and activities, so that, if he is known at all, it is for individual buildings that often do not seem to have a common style or signature. This is especially true for his work in Frankfurt, which – apart from the Central Market – has in the past often been treated as more or less anonymous utility architecture or subsumed under the Ernst May housing developments. After May’s departure for the Soviet Union, Elsaesser was furthermore blamed for May’s cost-overruns, leaking roofs and other planning defects: complaints which the politicians had been too intimidated by May’s towering figure and authoritarian bearing to voice face-to-face. Elsaesser, however, was not alone in being attacked and pilloried, to the point of eventually handing in his resignation on Jan 31st, 1932. As the economic crisis began to bite, and Frankfurt’s finances deteriorated, Landmann’s coalition came under pressure from the nationalist and national-socialist right, and Landmann himself was the target of ever more personal attacks. Facing death threats, he too resigned, in March 1933, weeks before the municipal elections returned a Nazi-majority to the city council. A vicious press campaign preceded both these resignations. One particularly personal attack accused Landmann of megalomania, comparing him to the Master of Metropolis from Fritz Lang’s film, but drew exclusively on Elsaesser’s sketches as proof of Landmann’s authoritarian despotism.5

The City as Social & Cultural Organism

The hate campaign shows – by way of a negative foil – that Landmann’s plans for a Greater Frankfurt were bound up with Elsaesser’s designs, which until now have either been ignored or treated as the airy fantasies of an underemployed architect. If, however, we factor them into the broader Landmann scheme of Frankfurt as a living organism and urbanist symbol of Modernity, then Elsaesser’s unrealized buildings, along with the ones that were built, emerge as a fully articulated and coherent overall project, in which Elsaesser – alongside Ernst May – would have been the key architect of Frankfurt Modern. Consider the following aspects of the Landmann concept, and align them with Elsaesser’s built and unrealized buildings:

– Health: Clinic for Nervous Disorders, Niederrad (Elsaesser, built), Swimming Pool, Fechenheim (Elsaesser, built), Municipal Swimming Pool, Main-Ufer (Elsaesser, not realized), Emma-Budge Heim (Mart Stam, built), Germania Boat-house (Elsaesser, built)

– Education: Konrad Haenisch Schule, Ludwig Richter Schule, Volksschule Römerstadt, Holzhausenschule (all Elsaesser, built), University Library (Elsaesser, not realized)

– Nutrition: Grossmarkthalle, with Schulspeisung (Elsaesser, realized), allotment gardens (Leberecht Migge, friend and collaborator of Elsaesser, realized)

– Recreation: Palm Garden Society House (Elsaesser, realized), parks (Max Bromme, realized, Max Cetto, realized)

– Spiritual Needs: Gustav Adolf Church, Nieder-Ursel (Elsaesser, realized)

– The Arts: Pavillion for the Music of the World Festival (Elsaesser, realized, temporary), Kunsthochschule (art academy: Elsaesser, not realized).6

This leaves very few of Elsaesser’s buildings and designs unaccounted for. One is his private villa in Frankfurt Ginnheim, but this was mirrored and matched by Ernst May’s private villa, a few hundred meters away. Built on land given to them by the City, the villas underscored their leading role and visibly established their parity as the twin heads of the city’s urban planning and civic engineering departments.

Job Creation: I.G. Farben

The other – unrealized – project was a joint Elsaesser & May submission for the new company headquarters of the I.G. Farben. Not a public works project, and therefore submitted by them as private architects, this landmark building is nonetheless crucial to an understanding of Landmann’s Frankfurt Modern vision, because it draws attention to that part of his strategy which I have so far neglected, namely the importance of job creation in the overall scheme, wooing major firms to establish their Headquarters in Frankfurt. Considered from today’s perspective Landmann was trying to implement the kind of cluster concept we are familiar with from contemporary cities, when they rebrand their assets, by transforming themselves into high-tech hubs, in the hope of attracting young, highly educated professionals, seducing them with “quality of life” bonuses like good infrastructure, as well as all the provisions and amenities I’ve listed as Landmann’s priorities: education, health, nutrition, recreation and the arts. In this sense, the Central Market building from 1928 and the I.G. Farben building from 1931 are the two signature projects which respond to each other in Landmann’s scheme of things, where civic planning and civic finance both complement and necessitate corporate investment and industrial self-representation.

How did the IG Farben building come to Frankfurt? In November 1925, under pressure from American competition, various chemical firms – among them the three market leaders Badische Anilin und Soda Fabrik (BASF), Hoechst, and Bayer, decided to form a trust – the Interessen-Gemeinschaft Farben (IG Farben for short). In order to remain competitive internationally, but also increase the visibility of the new conglomerate, the members of the trust decided on a physical consolidation. Given that the main partners were geographically dispersed in Ludwigshafen, Leverkusen and Hoechst, it seemed opportune to meet halfway, and to ensure that the new location was well connected and central. The choice fell on Frankfurt, not least because of the enormous effort the city had made to profile itself as a European metropolis. Landmann, for his part, was quick to spot an opportunity and offered the new industrial giant favourable terms: making a site available, granting tax conces¬sions and rights of way – in short, persuading this large employer to make Frankfurt not only its corporate headquarters, but to do so in style. To quote from an essay by Peter Schmal and Wolfgang Voigt:

“The desire for action on the part of I.G. Farben was most welcome in a Frankfurt, whose civic dynamism was matched by its ambitious but also costly investments. To become the ‘capital of chemicals’ meant more than acquiring a new title. Attracting the I.G. Farben meant that Frankfurt was able to claim one of Germany’s most technologically advanced industries. In the summer of 1927, the enterprise acquired an extensive park area from the Rothschild family at the northern rim of the West End. The city agreed to a land-swap, adding the adjacent grounds on which stood the old mental hospital, and it also approved the construction of 1600 housing units for the employees expected to move to Frankfurt.”

It is easy to draw parallels between the accommodating city council of 1927 which provided the I.G. Farben with a large area of desirable real estate, and an equally willing city council in 2007 which smoothed all the bureaucratic obstacles and legal hurdles, in order to make the site in Frankfurt’s East End, where the now decommissioned Central Market was located, as attractive and appealing to its favoured client as possible. What the chemical giant was to Frankfurt in the late 1920s, the financial giant is to Frankfurt in the 2010s. For the ECB, too, will create a large number of new jobs and boost the city’s housing stock, but also upgrade a whole district and neighbourhood of Frankfurt, in dire need of renewal.

How the IG Farben building was to be commissioned – whether by public tender, by inviting a pre-selected group of architects to submit proposals, or by drawing on the companies’ own in-house planning department – is instructive. It seems that the I.G. Farben Board quickly decided that the project was too big for their own architects, but in a face-saving move, so as not to antagonize them, an expert commission was formed, mostly of architects in their 60s, and thus from a previous generation, very different from the Weimar Republic’s young Turks. At the same time, Fritz Wichert, the very influential director of Frankfurt’s art and craft school, offered himself as a go-between, to mediate between Landmann and the I.G. Farben directorate, requesting that the leading Frankfurt municipal architects – i.e., May and Elsaesser – should not be excluded from consideration, underscoring the degree to which Landmann saw the new headquarters as part of his own master plan. In the end, I.G. Farben agreed, and besides May & Elsaesser only four more architects were invited, one of whom – Paul Bonatz – had actually been part of the original commission, while the others were Friedrich Höger from Hamburg, Jakob Koerfer from Cologne and Hans Poelzig from Berlin. Very quickly, it emerged that only Höger and Poelzig were serious contenders, with Poelzig’s plan the eventual favourite.

The IG Farben building, when completed in 1931 was impressive and innovative, and its historical significance was immediately recognized, not only because it dominated the well-to-do part of Frankfurt like a royal castle. Reporting on the opening, a journalist wrote: “Apart from the actual purpose of being an administration building, a place of work for 2000 thinking people, through whose hands run the invisible threads of a mighty corporation, the complex had to have a higher purpose. It had to be the visible emblem that could express the spiritual and material power that is this new company. Not only for today, where we contemporaries readily sense its meaning, but for tomorrow. This building casts its shadow into the centuries to come and speaks of the might and greatness of the enterprise, long after its time has passed.”7

In light of the slave labour camp Manowitz and the poison gas Cyklon B. which are now associated indelibly with the name of the IG Farben conglomerate, the choice of the word “shadow” strikes an ominously apt note, just as the phrase “long after its time has passed” has come true in a manner surely not intended, given that after 1945 IG Farben was kept alive mainly in order to be legally answerable to compensation claims, until in 2012 it was finally struck from the company register.

How did the IG Farben building introduce itself to the city of Frankfurt? To quote an architectural critic: “The park area between the main building and the casino with its broad steps and water basin makes one think of a baroque palace. Other features support the idea of a conscious use of baroque style elements by way of an imperial gesture […]. In contrast to a baroque palace complex, however, the connection to the city is missing: The central axis has no continuation into the urban space and is not related to the existing network of roads leading up the building. […] This is obviously an intended effect: The building in its majestic expanse is fully aware of its importance and keeps the city at a respectful distance. It clearly feels no need to refer in any way to its environment […]. The compact block of the building, its uniform height and protruding bastions formed by the traverse wings are reminiscent of a fortress that defends against the city. Poelzig does nothing to mitigate this effect, on the contrary: both the horizontal concave expanse and the natural stone cladding [hiding the steel skeleton] emphasize the quasi ‘fortified’ perception evoked by the building from the outside.”

Highlighting the building’s expression of power and its gesture of setting itself off from the city becomes even more pertinent, when contrasted with the plans submitted by May and Elsaesser, if we take these as representatives of Landmann, facing the challenge of finding appropriate symbols of economic power and industrial might, while also acknowledging its role as part of the city.

The May-Elsaesser plan shows a family resemblance with the Central Market, but its main feature is how the ensemble opens up to the adjacent streets and housing blocks surrounding the park area. As Elsaesser points out in his accompanying text, his two priorities were to ensure the building’s embeddedness into the city’s fabric, and to create the required two distinct routes of access, without them having the discriminating character of front entrance/rear entrance: “the difficulty and appeal of the task was to create a building that was substantial, but not too massive, which could follow the contours of the terrain, while nonetheless proportionate to the overall size of the site, generate multiple transitions with the existing buildings and street layout. The effect of the building’s mass is increased in a natural manner by the rising terrain. This allows for the different pathways of approach: from the south one reaches the official entrance for the Directorate and for representative functions; civil servants and employees enter the area from the east side, where the main road and tram lines pass, and where the car parks and bicycle shelters are located.”

Evidently, the May-Elsaesser design did not make it into the final round – it received 3rd prize – and thus considerations other than Landmann’s prevailed. It has since emerged that on the side of IG Farben, one individual was the key figure in many if not all of these decisions, including the (apparently foregone conclusion) that Poelzig would be the architect of choice. This individual was Georg von Schnitzler, one of the company’s senior directors, and a prominent patron of the arts, who had recently relocated to Frankfurt by acquiring one of the villas on the extremely upmarket West-End Square as his new home. Von Schnitzler’s preference for Hans Poelzig– a well-known architect of representative buildings who had recently completed the “Haus des Rundfunks” (Radio City) in Berlin, but with no previous connections to Frankfurt, having mainly been responsible for buildings in Breslau (Wroclaw) and Berlin – von Schnitzler’s preference is especially intriguing, since only the year before, von Schnitzler had worked closely and indeed intimately with another renowned architect, Mies van der Rohe.

In his capacity as representative of the Deutsche Reich for the Barcelona Universal Exhibition of 1929, von Schnitzler had delegated to Mies the artistic direction of the German exhibits as well as commissioning him to design a pavilion: the subsequently world famous and since 1986 reconstructed Barcelona pavilion. In this context, Lilly von Schnitzler had invited Martin Elsaesser to Barcelona’s German Week as her personal guest, where in October 1929 he gave a lecture on “Problems in Modern architecture” to the Europäische Kulturbund, of which the von Schnitzlers were supporters and patrons. As a “thank you”, Elsaesser gave a few guided tours to distinguished guests from Germany, trying to explain to the perplexed visitors of the pavilion some of the basic ideas and subtleties of Mies concept of architectural space. Elsaesser knew the von Schnitzlers well, since they had commissioned him to re¬design the interior of their newly acquired West-End villa, which Lilly wanted to turn into a “salon” and a showcase for the paintings of her protégé, Max Beckmann. Elsaesser complimented Lilly by writing an article about her house, praising her taste and residential style, for the fashionable weekly Die Dame, whereupon she returned the favour by contributing a short article “What I expect from my architect” published in Elsaesser’s 1933 monograph.

The interesting question is why Georg von Schnitzler, on a friendly footing with two renowned architects, considered neither Mies van der Rohe nor Martin Elsaesser seriously for the IG Farben commission. Although in retrospect it seems that the von Schnitzlers probably showed sound judgement in the distribution of tasks (or division of labour) for their respective architects – Mies for the World Expo Pavilion, Elsaesser for the modernization of their classicist villa, and Poelzig for his company’s headquarters representational building, at the time, among the architectural profession – if the journal Die Baugilde is to be trusted – the May-Elsaesser plan was much more extensively discussed than Poelzig’s design, considered conventional and derivative (for instance, of Albert Kahn’s Detroit buildings).8

Die Europäische Revue

With Georg von Schnitzler and his wife Lilly, another constellation comes into view, which gives a clue to the cultural climate of Frankfurt in the 1920s and 30s, because it opens a window on the close relations between industrialists, city officials and representatives of modern art and architecture, at a time of social upheaval, when the balance of power between elected politicians, so-called old money and the new economic elites had to recalibrate. These circles – which included the various architects and artists who enjoyed the von Schnitzlers’ patronage – promoted an idea of Europe that was intended as a counterpoint to the bourgeois nation-state, as it had re-constituted itself after WWI and the Russian Revolution. The alliance – manifested in the Kulturbund and its journal Europäische Revue – is not without its parallels to a more contemporary alliance, insofar as it wanted a Europe of economic, technocratic and intellectual elites who had to protect the continent – at that time from “Americanism” culturally, and Bolshevism ideologically. Each group wanted a Europe without borders, but for different reasons, and they were united in their dislike of party politics, which is to say, democracy. Obviously, today the antagonists are different, but a Europe of the elites, with as little popular participation as possible, is once more much in evidence among the guiding lights of the European Union.

Through Lilly von Schnitzler, for instance, Martin Elsaesser came to know the economist Alfred Weber and he met Karl Anton Prince Rohan, editor of the Europäische Revue. Elsaesser joined the Kulturbund, an association of German, Austrian and French intellectuals who supported a cultural reconciliation between France, Italy and Germany. The authors of the Europäische Revue, ideologically affiliated with the Kulturbund, included names such as Rainer Maria Rilke, Stefan Zweig, Paul Valéry and Julius Meyer-Gräfe, while among the speakers at the annual meetings of the Kulturbund were Thomas Mann and Hugo von Hofmannsthal, the literary scholar Ernst Robert Curtius and the architect Le Corbusier. Elsaesser and his wife attended the meetings in Frankfurt and Heidelberg in 1927 and were in Prague in 1928, which explains their presence in Barcelona in September 1929. The contacts with the Kulturbund and the Europäische Revue also give a clue to why Elsaesser, after being forced out in Frankfurt, sought an audience with Mussolini in Rome, and indeed was granted one, even though nothing came of it: Prince Rohan and his friends saw Italian fascism as setting an example for a Europe of strong nation-states, and architects initially considered Mussolini a champion of modernism: both Walter Gropius and Mies had tried for commissions there, when Hitler’s Germany no longer proved a viable field of activity. Such was the ideological volatility around 1930s that in 1932 the Europäische Revue would publish a celebratory issue on 10 Years Italian Fascism and a few months later, a special issue on Die Judenfrage in which prominent Jews like Leo Baeck, Arnold Zweig and Jakob Wassermann published articles alongside those of Werner Sombart, “Jüdisches Wesen im Dienste des Kapitalismus” or “Die Juden und die Literatur”, by Joseph Nadler, an early member of the NSDAP and an advocate of racial theories of literature.

In retrospect perhaps dangerously naive, the conservative values of the Kulturbund evidently seemed to some eminent minds Europe’s best hopes between socialism and capitalism, although an industrialist like von Schnitzler knew very well how to combine IG Farben’s own priorities of an expanded European internal market, free of customs and import restrictions, with lofty arguments about Western cultural values. Again, it is possible to argue that von Schnitzler’s financial support for the Kulturbund is in line with tendencies of the European Union, and in particular with trends since the introduction of the euro and the financial crisis of 2008, as the Union is moving towards a Europe of technocrats and business elites, while funds for cultural cooperation, multicultural understanding and the annual European capitals of culture are the lubricants meant to compensate for the democratic deficit vis-à-vis its citizen.

From I.G. Farben to Poelzig Bau

I come to my conclusion: In a way, it was the Americans, who by taking possession after 1945 of both the I.G. Farben Headquarters and the Central Market, highlighted the buildings’ strategic benefits for Frankfurt and symbolic significance beyond. The Central Market, partly destroyed by aerial bombing, became the US military’s regional storage depot and distribution centre from 1946 to 1954, before once more serving as the city’s fruit and vegetable market until 2004. Until recently, a plaque recalled an earlier re-appropriation, when – from 1941 to 1944 – the Central Market became the collecting point for Frankfurt’s Jews prior to deportation by train to the East: a mis-use, whose memory the new owners now have to add to the costs of restoring what remains of the original building, so that it can be part of the historical heritage its listed status entitles it to.

As to IG Farben, Georg von Schnitzler went before the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg and was sentenced as a war criminal to five years imprisonment, of which he served one. When, in 1995 the US authorities handed back to the Federal Republic the IG Farben complex – for almost 50 years known as the Creighton Abrams Building – the site was not only in urgent need of repairs, but also had to bear and repair other historical legacies. In May 1972, for instance, the building was the target of a terrorist attack by the Red Army Faction, which resulted in one dead, several wounded and the destruction of part of the casino. Such was the burden of history that no federal or regional agency was prepared to take on the IG Building, until the German government more or less donated it to the University of Frankfurt, with the name of Frankfurt’s most illustrious son emblazoned over the portal. The building itself is now known as the Poelzig Bau, perhaps in the hope that such dual re-assignation of ownership – Johann Wolfgang Goethe and Hans Poelzig – might help redeem its history and cleanse the nefarious legacy.

Prior to the university taking over the building, the last potential client declining the offer was the European Central Bank, which makes it quite ironic that its new headquarters should now be towering over (as well as taking over) the Central Market, bringing two of the pillars of Ludwig Landmann’s Frankfurt Modern into a dialogue of sorts, and suggesting that retroactively, it is German history itself that has become the owner of both edifices, their new purpose at once a re-branding and a revival of this history. If the Poelzig building and the new ECB premises have henceforth more in common than their monumentality, it is because across their mutually interrelated stories, the bright as well as the darker sides of Landmann’s vision for a Frankfurt Modern at the heart of Europe once more shine through, holding out a challenge that the occupants as well as the blockupiers need to face up to and hopefully can make good.

Notes

For a history of Das Neue Bauen, see for instance Norbert Huse, Neues Bauen 1918 bis 1933. Moderne Architektur in der Weimarer Republik, München, C.H.Beck, 1975.

See Günter Uhlig, “Stadtplanung in der Weimarer Republik: Sozialistische Reformaspekte”, NGBK (Neue Gesellschaft für Bildende Kunst, ed.), Wem gehört die Welt?, Berlin, NGBK, 1977, pp. 50–71.

Die Steuer beruhte auf einem Vorschlag des Berliner Baustadtrates Martin Wagner für einen Lastenausgleich, mit dem die Eigentümer von Immobilien an den Kosten des öffentlich geförderten Wohnungsbaus nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg beteiligt werden sollten. Durch den Wertverlust von Hypotheken aufgrund der Hyperinflation bis 1923 waren Grundeigentümer zuvor praktisch vollständig entschuldet worden, während ihr Grundeigentum durch die Inflation nicht an Wert verloren hatte.

Vincentz, Curt R.: Bausünden und Baugeldvergeudung, Hanover 1931–2, quoted from Teut, Anna: Architektur im Dritten Reich 1933–1945, Berlin, Frankfurt & Vienna, 1967, pp. 55–6.

Zur Jahreswende 1932/33 präsentierte der Generalanzeiger, damals Frankfurts auflagenstärkste Zeitung, seiner Leserschaft auf einer reich bebilderten Seite „Frankfurter Luftschlösser – die beinahe Wirklichkeit wurden“. 1. Die Abbildungen zeigten die Skizzen für einen „Turm des Magistrats“ und einen „Bücher-Wolkenkratzer“ als Studien für ein Rathaus und den Neubau der Zentralbibliothek. Sie entstammten einem gerade erschienenen Buch über Martin Elsaessers Bauten und Entwürfe aus den Jahren 1924–1932, also vornehmlich aus seiner Zeit als Leiter des Frankfurter Hochbauamts. 2 Höhnisch, nicht etwa ironisch, war diese Präsentation der „Traumstadt Landmann-May-Elsaesser“ im Generalanzeiger gemeint. Es war nicht nur ein Nachtreten gegenüber Elsaesser und dem ehemaligen Hochbau- und Siedlungsamtsdezernenten Ernst May, der Frankfurt noch eineinhalb Jahre früher als Elsaesser, nämlich bereits 1930, verlassen hatte. Die Abrechnung des Generalanzeigers mit den Bauvisionen Elsaessers zielte auch auf den seit 1924 amtierenden Oberbürgermeister Ludwig Landmann, der das Neue Frankfurt politisch erst möglich gemacht und die Stadtentwicklung in eine Phase der Expansion voller innovativer und weit reichender Entscheidungen geführt hatte.

“Landmann saw the arts, particularly music, as providing a classless common ground free of political and class strife, open to the enjoyment of all and offering the basis for a new unity in urban society.[…] Music appears to have been Landmann's special passion. Musical events in Frankfurt such as Musik im Leben der Völker and Sommer der Musik were heavily subsidised by the city – their funding and the subsequent deficit caused something of a scandal – but won international recognition. Under Clemens Krauss, another of Landmann's appointments, the opera flourished. Although the management remained wholly in Krauss's hands, Landmann is said to have used his official visits to Berlin and elsewhere as talent-spotting occasions in search of even better singers for ‘his’ opera.

Knoll, Georg Friedrich. In: Die neue Zeit, Jan./Feb. 1931, zitiert nach Cachola-Schmal/Voigt, „Immer eine große Linie“, in Pehnt/Schirren, S. 112.

By way of a footnote, May’s journal Das Neue Frankfurt only had harsh words for Poelzig’s monumentality, and for the rest, simply ignored the completed building, as it had already done with Elsaesser’s Central Market.