The Past and the Posthumous

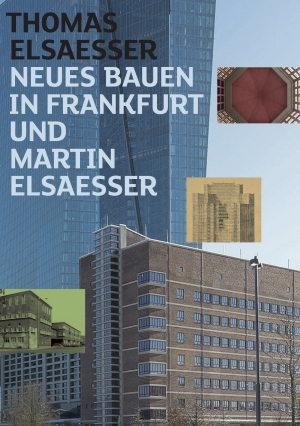

In 2007, through circumstances not entirely of my own choosing, I found myself resurrecting a family ancestor, my grandfather, the architect, Martin Elsaesser.1 I was asked to write a biographical essay for a catalogue accompanying a retrospective of his work at the Deutsches Architekturmuseum Frankfurt. The exhibition honoured him as one of the chief city architects in Frankfurt between 1925 and 1932, during the peak years of what came to be called Das Neue Bauen.2 His key building from the period, the Frankfurt Central Market, had been acquired by the European Central Bank in 2004 as the site of the Bank’s new headquarters. Although a listed building and therefore protected as a national monument, the Grossmarkthalle was under threat: the plans envisaged by the Central Bank – along with the notoriously deconstructionist impulses of the star architect designing the ensemble – meant that the integrity of the building, and thus its value as a historical landmark had to be sacrificed.3 The general context of the retrospective was therefore as much an act of compensation or restitution as it was of celebration and recognition: the temporary nature of the exhibition and the online existence of the Foundation had to substitute for the physical survival of the architect’s most famous building.

These, at times, painful encounters with an all-but-forgotten past and its retroactive reappearance, touched on several general issues.4 For instance, I had to ask myself what does it mean to claim for someone the status of the posthumous? According to the dictionary, posthumous refers to something ‘arising, occurring, or continuing after one’s death’,5 such as an award being given to someone posthumously, or a reputation being shattered posthumously. In which case, it also connotes something more troubling than an afterlife, something to do with another kind of life after death: an unquiet, restless undead-ness, something unresolved or unredeemed that returns to haunt the living.

Such a version of the posthumous is introduced by Jeremy Tambling, in his book Becoming Posthumous.6 Tambling makes a distinction between writers and works we consider classics: immediately accessible, recognized as relevant today as they were in their time (he mentions Shakespeare and Jane Austen). On the other hand, there are writers or works that were ‘already not quite alive in [their] own time’, and whose afterlife requires or must benefit from a special kind of constellation.7 This would be the condition of the posthumous in the case of the extraordinary fame of Franz Kafka in the 1950s and 1960s, or of Walter Benjamin’s reputation since the mid-1970s.

The condition of the posthumous implies a special relation of past to present that no longer follows the direct linearity of cause and effect, but takes the form of a loop, in which the present rediscovers a certain past, to which it attributes the power to shape aspects of the future that are now our present. We are in the temporality of the posthumous, whenever we retroactively discover the past to have been prescient and prophetic, as seen from the point of view of some special problem or urgent concern in the here and now. In other words, we retroactively create a past and a predecessor, in order to assure ourselves not only of a pedigree, but to legitimate the present.

The particular constellation, which made the condition of the posthumous a pressing concern for me, thus went beyond writing the catalogue entry. To assist the curators of the exhibition, I had gone through my father’s family albums and photo collection in search of visual material that could illustrate my grandfather’s life. That’s when I came across my father’s home movies from the 1940s, which we saw as children projected on a makeshift screen. Remembering that some of them featured my grandfather, I managed to edit together two seven-minute video loops. These home movies proved a major attraction for the visitors; even though the time was ten years after his Frankfurt period, and the place appeared to be his summer house on an island near Berlin.

Tasked with establishing a Martin Elsaesser archive and with promoting the foundation, I decided the home movies might make a film that commemorates his life to complement the scholarly focus on his work in the catalogue and other publications.8 As a historian with a predilection for early cinema and some knowledge of German film history, I had already been publishing on non-theatrical films, such as industrial films and instructional films, including on documentaries about architecture and urbanism.9

We all dream of making our own Sans Soleil (Chris Marker’s seminal, moving, and poetic essay film) and I greatly admired Respite/Aufschub (2008), Harun Farocki’s found footage reconstruction of life in a Nazi deportation camp in the Netherlands in 1944.10 But I began to orientate myself more by the personal documentaries embedded in larger histories, for instance, those by Ross McElwee (Sherman’s March, 1985; Bright Leaves, 2003) and Alan Berliner (The Family Album, 1986; Nobody’s Business, 1996). I also studied Su Friedrich’s Sink or Swim (1990), Nathaniel Kahn’s My Architect (2003), and Doug Block’s 51 Birch Street (2003).

These films by professional directors and visual artists quickly made me realize that there was no way I was going to turn myself into a film-maker: I just needed to make a film. The problem: I did not have a story. Or rather, I had two stories that had little to do with each other: one set in Frankfurt, in the present, and centred on the fate of my grandfather’s landmark building, on the lawsuit, the protests, the out-of-court settlement, the exhibition, and the setting up of the foundation. And that other story which may or may not be hidden in the two hours’ worth of uncut home-movies material, mostly shot between 1940 and 1944, and set in and around Berlin.

This other story involved not just my grandfather, but also my grandmother, my father, his two sisters and younger brother, my future mother, her brother, and their mother. Overshadowing these members of my extended family was another person, also an architect, and my grandmother’s great love and long-time lover, Leberecht Migge. Anxiety over my family-centred self-indulgence was aggravated by the fear of indiscretion – of betraying the dead, rather than rescuing them: feelings which I tried to keep at bay by persuading myself that there were extenuating circumstances and mitigating factors that had forced my hand. First, both my grandfather (entirely thanks to the ECB’s controversial plans for their acquisition) and my grandmother’s lover (rediscovered as one of the fathers of the green movement in Germany because of his fervent advocacy of urban gardening, waste recycling, and ecological sustainability) had attained a certain topicality. Second, another protagonist, my grandmother, perhaps deserved a place in posterity and in the public domain, precisely because she is just one of the many women from the first half of the 20th century who were instrumental in bringing about changes in all kinds of fields, but who have remained in the shadow of their more famous, but often also more fallible men. For her, the posthumous comes as a way of making amends, or, in the words of Hannah Arendt: such posthumous fame is ‘the lot of the unclassifiable ones […] those whose work neither fits the existing order nor introduces a new genre that lends itself to future classification’.11

The Essay Film

Even if not conceived as an essay film in the manner of Marker or Farocki, I still wanted to sustain a personal point of view that relied less on the single voice – embodied in the obligatory off-screen commentary – but instead present a subjectivity that was manifest more in the tonality of the tentative exploration, in the cautious steps moving forward, across briefly glimpsed traces of past events, while interrogating the historical footage, yet letting the images speak about what they wanted to say (or carefully tried to hide). But I also intended to question the epistemological status of the home-movie scenes – whether caught on the fly or carefully staged: their truth status and evidentiary force. I wanted to involve the spectator in the process of discovery, as well as borrow the essay film’s constitutive reflexivity and self-reference. Reflexivity, in that I am not just showing these images because they evoke a bygone age, or present my family as if still alive: I am representing this footage for a purpose, even if I did not yet quite know what this purpose was. And self-reference, because these images are the material residue of an act of filming, itself inflected by intention and purpose, and not pretending to deliver transparent access to the reality they depict, or open a window on a world as it once was, and that is now lost forever.

The editing phase was productive (and painful) in that it made me focus on the differences between documentary, essay film, and home movie, as well as between making a film for myself and making a film for television. And it obliged me to think more critically about the relation between today’s film culture and practical film-making, as the distinction between amateur and professional has become less a matter of craft and inspiration, and more a matter of capital and resources; less about access to tools and technology and more about access to institutions and insiders. In short: when – thanks to digital software and the Internet – everyone can be a film-maker and upload their work on Vimeo or YouTube, what is an author, what is art, and what is self-advertising? Acting on behalf of the Martin Elsaesser Foundation to promote its goals, my task was to access the institution, which is to say, television and, through television, try to reach the public sphere, and not to claim avant-garde status or to expect auteur treatment.

Lieux de Memoire between the Materiality of Memory and Historical Topographies

If now – after many screenings of the film and after its television broadcast – I return once more to the external circumstances and posthumous constellation that made me make The Sun Island, it is to resume my role as film historian and theorist. I had begun to draw some further conclusions about the stakes involved, when utilizing found footage, incorporating amateur film, or when grappling with the ethics of appropriation.12 On the face of it, The Sun Island belongs to the by-now almost clichéd genre of the ‘family film’, in which sons or daughters make a film about their fathers, mothers, or parents, by sifting through home movies, letters, and family albums that have been passed down to them. Often, in such films, the memory of the dead becomes a mirror for the film-makers’ fragile egos: to study who they are, to ponder the roads not taken, or to reflect on what they have become. The genre, therefore, is part of the broader movement of identity politics: we are a culture mindful of our precariousness, fearful for our future, and are forever searching for ‘roots’. Yet, for this self-scrutiny or self-affirmation, we increasingly draw on audiovisual sources, as the lived embodiment and visible complement to the genes, the bloodlines, and DNA that biologically bind us to past generations.

The Sun Island (Thomas Elsaesser, Germany, 2017), still. © DFF

On the other hand, the quest for roots and personal identity is, in turn, embedded, especially in Europe, in the general memory discourse, which, in Germany, is inescapably shaped by and caught up in the various ‘mastering-the-past’ cultures of commemoration, beginning in the 1970s but taking off in earnest after reunification in 1990.13 And, while in my case, there was no ‘quest for personal identity’ that initiated the film, it would have been foolish of me not to own up to the memory and identity discourses that The Sun Island now finds itself part of. Indeed, one of the outcomes of the give-and-take between the producer and myself was that the film became ever more ‘personal’, even autobiographical: fully cognisant of the fact that it had to be the ‘family film’ genre which would serve as the matrix of recognition by which a German television audience could make affective and interpretative contact with The Sun Island.

One of the strongest discourses of memory and remembrance since the 1990s has been Pierre Nora’s notion of the ‘lieu de mémoire’ (the site of memory).14 On a much smaller scale, both temporally and geographically, but partly inspired by Nora, I tried, in The Sun Island, to reconstruct, but, in the end, also to invent, the memory map of an ‘île de mémoire’ (an island of memory), based on this actual island located not far from Berlin, where, to quote Marina Warner, ‘ecology and stewardship’ were ‘interconnected with memory and stories’.15 This particular lieu de mémoire appears to the eye – and from the air – as a site of pristine nature, but turns out to be a site that bears its own scars of memory and traces of a once-lived history.

In the course of plotting and recording these slow cycles of regenerative destruction, I discovered several other cycles of value creation and value destruction, binding together nature and culture. It turned out that the photographs, letters, administrative records, and home movies from which I had to piece together the story of The Sun Island, both metaphorically and literally, prolonged this transfer of decay and regeneration, insofar as, especially my father’s home movies and my grandmother’s letters, gave another twist to the human-history/natural-history interface, when I began to restore decaying film stock and had to decipher Gothic script. Digitizing both the images and the letters added another layer to the value exchange: the gain in legibility was a loss in authenticity, and yet, it is invariably the intervention of a new technology that confers added value to an object’s obsolescence.16

The Sun Island as a lieux de mémoire is intimately linked to another historical topography: Berlin. Berlin has engendered its own cultural memory, made up of images and music, buildings and ruins, clichés and discoveries, fiction and critical discourse. As almost everyone writing about the city notes, it is a very peculiar kind of chronotope.17 In fact, ever since the nineteenth century, Berlin has been a city of multiple temporalities, and of diverse modalities: virtual and actual, divided and united, created and destroyed, repaired and rebuilt. Living in a perpetual mise en scène of its own history, a history it both needs and fears, reinvents and disowns, Berlin is a city of superimpositions and erasures, full of the ghosts and ‘special effects’ that are the legacy of Nazism and Stalinism, obliged to remember totalitarian crimes while still mourning socialist utopias.18

What Marina Warner presumably also means by ‘stewardship’ – and it applies with singular force to film, one of the most physically fragile and yet imaginatively powerful archives of evidentiary ‘presence’ – is stewardship as a form of trust, nowhere more so than in my particular instance, where most of the materials I depended on for The Sun Island film do not belong in the public domain, but are, in every sense, ‘private property’. Not only is the island private property (which I ‘trespassed’, when filming there), but the home movies and amateur photographs – which I complemented by drawing on personal correspondence, love letters, and poems – concern public persons at moments when they were at their most intensely private and vulnerable.

Yet the realities they document also belong to a collective ‘history’, insofar as these letters and movies, these literary and photographic tokens of friendship and rivalry, of courtship and passion, of tragedy and trauma, are also the only extant evidence and testimony to an ‘experiment in living differently’: Migge’s project of urban self-sufficiency, refuse recycling, and of a maintenance-and-sustainability economy that was meant to be emulated, propagated, and made public. In inspiration, location, and implementation, the island experiment thus belongs to the history of Berlin and of German modernism, to the extent that one family’s filmic memories can mutate and metamorphose into a historical topography.

The Home Movie as Discourse and Practice

It is partly this historicity and the peculiarly specific acts of symbolic transfer and material-immaterial exchange, which – in my contest with the producer over the film’s formal structure and narrative arc – persuaded me that it was ultimately in the film’s best interest not to insist on making it the sort of essay film I had once imagined and had even sketched out on paper. Instead, it is worth examining more closely the original discourse and practice into which my father’s films inscribe themselves, before they became The Sun Island, namely, that of the home movie. Here, then, are some of the defining criteria, as well as the points of contention that arise when home movies are re-edited, repurposed, and re-presented.19

How Do We Identify and Recognize a Home Movie?

Roger Odin, probably the world’s foremost scholar of home movies puts it crisply and succinctly:

Nothing resembles a home movie as much as another one. […] The same ritual ceremonies (marriage, birth, family meals, gift-giving), the same daily scenes (a baby in his mother’s arms, a baby having a bath), the same vacation sequences (playtime on the beach, walks in the forest) appear across most home movies.20

In this respect, the footage left to me by my father answers very precisely to this description: he recorded family meals, several birthdays, and different leisurely pursuits. Prominent in these home movies are the Boccia games so beloved by my grandfather, a volleyball game when my father’s work colleagues came for the weekend, and, as for playtime on the beach, there is the frolicking in the lake, caught in glorious Kodak colour by a camera at water level. Regarding ‘a baby in his mother’s arms, a baby having a bath’: these scenes, too, are duly present. It is as if Odin was describing my father’s films, but that is exactly the point he is making: he has seen them, because ‘once you’ve seen one, you’ve seen them all’.21

Who Makes Home Movies?

Odin also offers a definition of the home movie as a family film (in French, home movies are ‘films de famille’), namely ‘a film that is contrived to function within the space of familial communication: it is made by one member of a family for the other members of the family, about the history of the family’.22 This, too, applies to my father’s material: 70 per cent of what I have takes place and was shot on the island, about 10 per cent on skiing trips in the Alps, and the rest indoors or at other locations.

Where my father’s home movies differ is that, traditionally, it is the father who films his own family and thereby affirms, consolidates, or enforces his own authority. In my case, it was the son who filmed the family, and, once he had his own family, he seems to have lost interest in filming. As it happens, the island was a matriarchal space, and my grandfather – the father figure who should have been behind the camera – had already given up or lost his paternal authority.

But ‘who makes home movies’ also points to another factor. In the 1930s and 1940s, portable cine-cameras were still a rarity and a luxury item, making home movies of that period indicators of a well-to-do bourgeois family. This is evidently the case with my grandfather, a renowned if unemployed and unemployable architect during the time in question. Yet his son – a passionate photographer, owner of an expensive Rolleiflex since his fifteenth birthday – seems to have acquired the cine-camera quite late, only once he had settled in his first real job and was earning a salary.

Since then, the class-index of home movies has all but vanished. The advent of video and the camcorder meant that anyone can and does make home movies, which may or may not affect their value as documents. The arrival of more affordable equipment and the exponential increase in the quantity of amateur film, has given their celluloid-based precursors, such as those standard 8 f ilm strips of my father’s from the 1940s, an extra distinction of scarcity value, quite apart from the fact that they were silent witnesses or unwitting observers of one of the 20th century’s most momentous and catastrophic historical decades. After the camcorder came the mobile phone: this latest shift in technology – taking movies with your smartphone – not only makes of home movies a corpus so vast that no human and only machines can keep track of their proliferation. It also confers on home movies from these earlier technologies yet another value: that of obsolescence, which registers as a precious materiality, a guarantee of authenticity, and a promise of pristine veracity, all gained through hindsight, and subject to the posthumous.

Who Speaks in the Home Movie and to Whom is it Addressed?

I’ve long puzzled over this question – whom do my father’s home movies address? Odin is quite clear and categorical: in home movies, the family speaks to itself about itself; they are entirely self-referential. But, inside this self-reference, there are nuances and enigmas, tensions and even contradictions. In my father’s case, it is possible and even likely that different events and circumstances occasioned the individual pieces of footage, because, with some notable exceptions, all of which I use in The Sun Island, the films are neither edited nor do they follow a discernible narrative arc. Odin offers a persuasive explanation:

To function well, the family film needs to be compiled as a non-organized succession of shots that present mere snippets of family life so that each member is free to construe the family’s story in their own way, while sharing a reconstruction of the family’s story with the other members. In summary, the family film must not have an author if it is to allow the family to speak across itself: this is its ideological function ‒ to produce a consensus in order to perpetuate the family.23

I shall come back to the question of authorship, but, what cannot be emphasized enough is that, in my case, the son and not the father shot the films. For a long time, therefore, I thought he used the island and the family as a mere pretext, because what really fascinated him was the wind-up cine-camera, the machine itself, and what one could do with the apparatus: especially given that he was an engineer by profession, and a bricoleur by passion. In the film, I point out that this may have predicated him for making home movies, the bridge being ‘montage in its original meaning’.24

However, this does not exhaust the possibilities of whom the home movies address. In The Sun Island, for instance, I tentatively make the case that my father used his camera to woo his future wife, who, at that time, was still nurturing the hurt of a broken engagement. As her letters attest, she was more attracted to the dashing writer who occasionally visited the island with his wife, and even to Sebastian (eleven years her junior) than she was to my father, whom she considered socially inept, chaotic, and nerdy. Three of the plainly ‘staged’ films are meant to win her over: one paints the idyll of a couple in love, the other shows them enjoying the domestic bliss of getting up on a sunny morning in their joint apartment, and the third has the two of them sharing Sunday brunch on the island.

While making the film, yet another possible addressee imposed herself: the short instruction films I call ‘docu-manuals’, which show Leberecht Migge’s patented settler implements in action – tent hut, cold frames, compost silo, dry toilet – are clearly meant to honour my grandmother’s dead lover, and are therefore addressed to her, by way of document, homage, and monument. At once very personal gifts, the historical value of these sequences is nonetheless considerable, since they confirm that the Sun Island was indeed an experimental laboratory station, and not just a love nest (during the 1930s) and a refuge (in the 1940s).

What is the Documentary Status of Home Movies?

Given the cliché situations and repetitions of events, the direct informational value of home movies would seem to be low. Home movies are a little like dreams: fascinating or troubling to the dreamer (the members of the family), tediously repetitive or inconsequential to anyone outside. Yet, the world at large (and not just film historians) seems to have recognized the documentary value of home movies in a variety of ways. To be noted is the remarkable migration of home movies and amateur film-making from the attics, shoeboxes, and flea markets to film archives, special collections, and institutions expressly set up to preserve such materials. One can easily list some two dozen archives in France, Germany, Belgium, Britain, the United States, but also in Cambodia, Australia, New Zealand, and Canada that specialize in home movies or amateur films. The same archival impulse animates institutions dedicated to regional history: important centres of home-movie collections in the United Kingdom, for instance, are the East Anglia Film Archive, the North West Film Archive in Manchester, and the Scottish Film Council. Then, there is a special urgency to preserve amateur film in countries that have suffered historical disasters – civil war, genocide, ethnic cleansing – which may explain the existence of the Bophana Audiovisual Resource Center in Phnom Penh (Cambodia), set up by the film-maker Rithy Panh, his country’s foremost director of films about cultural memory and national trauma.

Are Home Movies Counter Narratives?

In the case of Cambodia, as in many other countries, an interest in the archiving of amateur films and home movies may well be guided by the need to possess non-canonical representations and thereby also to collect non-official sources of information. These often serve in the salvage or construction of a counter-memory, which, in turn, can be a powerful instrument in uncovering forgotten, repressed, or obliterated events in the lives of nations or individuals. More than oral testimony and less than evidence before a court of law, such documents have a potency of their own when enlisted in struggles for minority rights or restorative justice, after civil wars, or religious or ethnic conflict. One of the reasons why there has been such an interest in home movies is that epithets such as ‘alternative’, ‘resisting’, ‘anti’, and ‘counter’ lend themselves quite readily for this corpus, in line with a more general tendency to ‘activate the archive’.25

Home Movies are the Sunday Edition

However, an equally productive approach to locating the ‘political’ significance might be to dwell on the discrepancy, so typical of home movies, between what is in the picture and what is kept off-frame. This can be extremely frustrating to historians, so much so that many professionals dismiss home movies as unreliable or even misleading evidence. Yet, the discrepancy can also offer unexpected benefits, since these gaps, once recognized as such, create openings in other directions. Quite generally, the intense public interest in home movies, family histories, found footage, vintage postcards, and photographs is not only due to a nostalgic appetite for a past we always imagine more authentic than the present, or to the hope of recovering there the voices of the silenced and oppressed. It also signals the broader cultural shift in favour of audiovisual, rather than written documents, as physical evidence for this past. We are now so used to having everything that matters recorded and stored in sound and images, that the written word, along with the material world, increasingly comes to be seen (and be used as) corroborating illustration of the audiovisual record. Gone is the time when images were regarded as merely the representation of a pre-existing reality, of which they were expected to be the faithful and truthful servants.

Such an almost ontological switch depends quite clearly on a different set of default values. The visual record will be preferred for its special qualities: of self-evidence, of immediacy, of presence and authenticity. These qualities are, of course, not necessarily historical or epistemological – indeed, they are primarily aesthetic. Once we accept that home movies euphemize, select, and filter, we can look for their ‘truth’ somewhere other than in their ‘representational’ veracity. They force us to shift from a realist paradigm to a different hermeneutic strategy: we need to develop special skills to read and interpret the visual record, perhaps especially in the case of home movies and other non-canonical materials from the archives and the attics. As Roger Odin puts it: it is always possible that ‘a film of minor importance can suddenly become a fabulous document when the historical context of reading changes’.26

If we are, indeed, in the aesthetic regime, as Jacques Rancière would claim,27 new frames of reference come into view: first of all, any re-viewing of home movies made 70 years ago – even prior to any editing and compilation – constitutes a reframing. Secondly, such reframing requires a hermeneutics that not only reads what is there, in the light of hindsight and present preoccupations, but also interprets absences as having their own kind of presence. Correspondingly, the challenge for the curator-film-maker when reframing home movies in their own work, is to make silences become eloquent, but not to fill them with words (or more images). A reading against the grain, a reading that engages the home movie or amateur film in what it does not say outright, means listening to what it cannot say, but nonetheless gives away or conjures up through absence.28

The Sun Island tries to be mindful of this challenge. For instance, the description of a horrific night of firebombing in Berlin, and an equally horrific incident of shot-down British pilots being left to rot in the sun on a Berlin square runs parallel with images of morning gymnastics on the island. More generally, the war, as, indeed, the entire Nazi regime, seems to be happening off-screen, and must be inferred from scant mention in the letters and a few words of commentary, such as the observation that we are in the third year of the war, and women now do men’s work, while we see three women in headscarves and aprons saw logs and chop firewood.

This virtual absence of the signs of Nazi rule and the war’s invisible presence on the island is both faithful to the material – there is no extant footage among my father’s films of military parades or street scenes with jubilant crowds giving the Nazi salute – and a deliberate aesthetic choice, hard-fought-for in my confrontations with the producer. I have been criticized for this, also by audiences, notably in Germany and Britain, though not in New York or Tel Aviv. The main argument is that I am too soft on my family, who seems to have survived the war unscathed, and that I do not press them too hard or come clean about their political views. I merely mention that one son was part of the occupying forces in Paris, that the daughters were in the compulsory Reich Labour Service, that the family’s writer-friend was killed by a partisan sniper in Italy, that my father served a few weeks in a communication battalion on Czech-Polish border, and that my grandfather was drafted into the Volkssturm, the local militia, in the last months of the war and spent time as a Soviet prisoner. ‘Where is the “Kristallnacht”, where the Jews brutally pulled out of their Berlin homes, where is Auschwitz?’ They ask. ‘Not in my father’s films’, I am obliged to answer. Let each member of the audience draw their own conclusion, for it was my experience while making The Sun Island that home movies give away most, when one lets them speak in their own idiom. Much of this idiom, as Odin reminds us, is celebratory in tone and tenor.

In The Sun Island, I call this ‘the Sunday edition of the family’. But given the polysemic nature of the filmic image, there is nonetheless enough evidence of realities outside – outside the frame and outside the island – to be found right inside the images themselves, if one cares to look. Historians speak of documents as providing witting and unwitting testimony.29 What is of interest here is the unwitting evidence – not necessarily in the sense of a ‘gotcha!’ moment, not even primarily about the Nazi regime, but merely pointing to some silent witness present, or to a shift in attention brought about by the distance of the 70 years that separates us from these images. To give just one example of the silent witness, providing unwitting testimony: in one scene depicting my grandfather reading the papers, a radio can be glimpsed on the shelf, which is unmistakably a Volksempfänger, the people’s radio, introduced by the Nazi regime in much the same way it promoted the ‘Volkswagen’, the people’s car. Except that the Volksempfänger was a propaganda instrument, but also a surveillance apparatus for the State. Its portable version, operated by batteries, without connection to the electricity net – and clearly the version used on the island – carried a warning: ‘If used to tune in to enemy broadcasts, owner will be liable to severe penalties, including prison.’ Indices such as these resonate with the notion that home movies have a special ‘reality effect’ because of their peculiarly ‘accidental relationship with history’.30

The Traumas

This accidental relationship must, in certain cases, be given a stronger reading: as the traces of a catastrophe that cannot but keep its origins and consequences buried. Another name for such disasters, which only manifest themselves in the form of accidents or parapraxes – slippages, non-sequiturs, chaotic or congested images – is ‘trauma’: a familiar trope in the discussion around the home movie. For instance, what in part occasioned (and animates) the collection Mining the Home Movie is the film Something Strong Within by Karen L. Ishizuka and Robert A. Nakamura, which deploys amateur film and home movies to document the traumatic impact of the WW II internment camps in California on Japanese families, of which the home movies’ apparent normalcy is the numb testimony. In a more theoretical essay, co-editor Patricia Zimmermann touches on trauma via the ‘repressed’, the ‘absent’, ‘failure’, and ‘unresolved phantasmatics’:

Amateur films do not deploy any systematic cinematic language. They reverse the relationship between text and context. Facts reveal fantasies, and fantasies expose facts. They present psychic imaginaries of real things, and figure material objects as psychic imaginaries. As a result, it is necessary to cross-section the sedimentary layers of historical context to deconstruct what is repressed and absent. Amateur films are often viewed as cinematic failures infused by an innocent naivety and innocence, a primitive cinema without semiotic density. Amateur films appear to lack visual coherence because they occupy unresolved phantasmatics. These lacks and insufficiencies create collisions between the political and the psychic, between invisibility and visibility.31

In the context of German home movies from the period I am concerned with, trauma is inevitable, and it is invariably linked to the Holocaust, or, more particularly, the trauma of the eviction, deportation, and destruction of hundreds of thousands of Jewish families and individuals from Germany. By contrast, the disasters that befell the Germans themselves in the last years of the war and in the years immediately after – the deaths of their loved ones in a senseless and criminal war, the firebombs that destroyed their homes, the mass expulsions from the East, the punitive rape of German women – this could not be discussed and certainly not dignified with the word ‘trauma’. Against this background, The Sun Island could be seen as part of a kind of revisionist rewriting, where the Germans are finally allowed to have their traumas and also feel like victims. Having written an entire book on these issues, I am, of course, more than aware of such pitfalls, and have been quite careful to make sure that the traumas in my film are of a very personal and private nature, having to do with love and betrayal, with a death foretold and inconsolable mourning – before these domestic traumas reveal themselves to have connections with the historical traumas after all, through my mother and maternal grandmother.

Framed by these different sets of references and reading contexts, several layers of hypothetical narratives emerged from the moments of life frozen in time and captured by my father in sometimes filtered, sometimes fortuitous images. The overall horizon referenced, is, of course, the Second World War, a concentration of an event of such enormous historical significance that their all-but-total absence from more than two hours of film is itself one of the most astounding fact about this footage. But, as pointed out above, there are ways of locating signs of presence, even in the absence of any visible evidence of how we picture Hitler’s Germany.

An important reading context touches on the role these films played within my own family: my sister and I, as children, grew up with these films. They were shown on holidays, birthdays, when guests came, or as a special treat. We loved the anticipation of the performance in the living room, the white sheet that was hung up as the screen, the home-made stand for the rattling projector, the tiny little reels, how delicately they had to be threaded up, and how often the projection had to be stopped, because there was a break in the brittle celluloid. I can still smell the acetate used to glue them back together.

I now know that we did not see all of the films, and, for us, as children, these moving images told the love story of our parents. It was especially thrilling to see our parents, before they were our parents, and to see them so happy and relaxed. By the 1950s, when we watched the films, this wasn’t always the case. Like most families, ours faced some very tough times, with my father out of work for several years, and us having to survive in very provisional accommodation on the outskirts of the industrial town of Mannheim. It took its toll on my mother and on the marriage. Surprisingly, my father never seemed to have bothered to edit the footage into some kind of coherent narrative; the reels were projected more or less as he had filmed them, and in random order, and without contextualizing commentary. From the late 1950s onwards, he lost interest in amateur movies, or found us as a family not that inspiring, and so, from the time I was in my early teens, the films faded from memory.

Only decades later did another layer come to surface. It was in 1989, when I wanted to pay tribute to my mother for her 80th birthday, and had asked my father’s permission to transfer the films to video. I put together a life of my mother in photos, and then made a compilation of the scenes from the home movies, where I thought the budding love between my parents became most apparent. To my deep disappointment, my mother was not at all pleased with my offering. As a surprise gift, we showed the film to a large gathering of friends and family, but my mother felt it was an unauthorized invasion of her privacy, that we had inadvertently revealed much more of her personal life than she was willing to share.

It was then that I realized that the island had been not just a location she happened to be during the war years, but a hideout, a place where she could recover, in the company of an older woman, from the pain of a broken engagement. As the daughter of a mixed marriage, she was not allowed to marry an Aryan, and her Catholic fiancé had broken off the engagement very suddenly, dropping her without word, making her wait and wait. With the help of her brother, a university friend of my future father, she found a new home on the island, shielded and protected from anti-Semitic persecution. In other words, inside the parental love story that we children thought we saw in the home movies, there was the personal tragedy and trauma of our mother. Something she obviously did not wish to relive or expose to the world. Now traumatized as well, I put the film material aside and did not touch it, until about fifteen years later, when embarking on the Sun Island film, I came to realize that, beneath my mother’s tragic love story, there was another love story, also tragic and traumatic: that of my grandmother.

This story also emerged by accident, around 2005, after a lecture of mine on Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927) and Slatan Dudow and Bertolt Brecht’s Kuhle Wampe (Who Owns the World?, 1932) at the Free University of Berlin. A young man from Philadelphia, David Haney, introduced himself to me afterwards, and asked if, by any chance, I was related to the architect Martin Elsaesser. I answered in the affirmative, and he then wanted to know if the name Leberecht Migge meant anything to me, since he was writing his PhD thesis on the garden architect Migge, and he had come across the name Elsaesser, as the city architect who had given Migge important commissions first in Frankfurt and then in Hamburg. I said I had heard about Migge, but not in connection with my grandfather, and more as the great passion and love of my grandmother. I vaguely remembered a hush-hush story that it was for Migge that my grandmother had left her husband and four children in the late 1920s or early 1930s. David was dumbfounded, because he had never heard about this liaison. All he knew was that Migge was a married man with seven children living in Worpswede near Bremen, where, supposedly, he had also died. The fact that he had actually died in a Flensburg clinic, with my grandmother by his side, remains hidden to this day, and is struck from the record. But, that his widow destroyed everything she could lay her hands on, in the hope not only of obliterating every trace or memory of the affair, but also of Migge’s life work, adds dimensions of anger and revenge, of despair and grief that certainly traumatized my grandmother until she slipped into dementia, but that must have traumatized the Migge family as well.

The Question of Authorship and Anonymity: Television and Art Spaces

Even though The Sun Island was made for television and with television money – which brought its own sets of constraints, some that were creative, some that had to be resisted – I had few illusions about the chances of securing theatrical distribution for my film, and I was well aware that television tends to use home movies in historical documentaries mainly because they are cheap. But television also exploits home movies and amateur productions as a shortcut to truth and authenticity, creating a kind of collusion with the viewer. Odin sums it up:

[Television shows] invite me to see these images as images shot by people ‘like me’ (vs. professionals). Since then, these images appeal to me differently: they possess an emotional force specific, a force that pushes me to accept them as they are, without questioning their enunciator in terms of truth (their origin is the pledge of their innocence). I call this the mode of authenticity, the mode which, while inviting me to construct or imagine a real enunciator, forbids me to question him in terms of truth.32

Questioning the enunciator is indeed a major problem when dealing with home movies. All too often, television instrumentalizes home movies to the point of ‘harvesting’ them for a whole range of authenticity effects. Yet, one wonders whether home movies fare much better when remediated and repurposed by film-makers or in installation pieces. There, too, the tendency is to anonymize them into found footage, to obfuscate their origins, the easier to manipulate the material and make it serve new objectives.

Yet, as Odin also reminds us: ‘the family film must not have an author if it is to allow the family to speak across itself: this is its ideological function (to produce a consensus in order to perpetuate the family)’.33 As indicated, this was true in the case of my father, who rarely edited the footage he shot, and it was true when screening the films among us family members: everyone talked, interjected, pointed out what was coming next, or started to tell an anecdote – except my father, who stayed silent: a mourner among the socializing family and guests.

In the films themselves, my father often put himself in the picture, as if to disperse the enunciative instance, but not unlike a director who stars in his own movie, perhaps his authorship is thereby claimed more effectively. I show my father ‘direct’ even when he is in the frame, and I show him entering the frame when the camera is on a tripod and already running.

But where do I stand? Am I using my father to appropriate the films, putting myself in his place, looking over his shoulder, retroactively guiding his hand by editing his ‘authorless’ films into a coherent narrative? Even if I didn’t make an essay film, did I manage to make an authored film after all? It is a legitimate question, to which I only have an oblique answer: The Sun Island certainly connects with my more academic work in many clearly discernible ways, since several of my own theoretical preoccupations converge with the film. First, The Sun Island relates to German cinema, notably Weimar Cinema and the transition to the Nazi period, where I suggest that, in matters concerning cinema, the rupture from politically progressive Weimar culture to repressive Nazi anti-culture is less clearly marked than one might imagine, notably in the genres of documentary, instruction, and propaganda.34 The Sun Island is also related to my research on family melodrama and trauma studies. Several people have responded to The Sun Island by calling it a family melodrama. Who are the heroes of this story? Each one a personal tragedy, each one has their reasons – much like the melodramas of Sirk or Minnelli that I wrote about in the early 1970s. Finally, my preoccupation with media archaeology plays a role in this film. In the film, I use the layer-upon-layer metaphor: I call it ‘unreeling and unpeeling’. It is also a sort of mise-en-abyme, by embedding the island story in the Frankfurt story: the ‘homecoming trope’ for me and the homelessness of Migge, but especially of Liesel – exiled from the island, and feeling like a widow next to her husband. Media archaeology is also present when material objects serve as internal indices and silent witnesses; for instance, the books briefly glimpsed as presents in the birthday scene. I managed to identify them, and this allowed me to ‘contextualize’ the scene. Other scenes I was able to synchronize with letters or postcards that had survived, permitting me to date and to locate certain film fragments, and, with them, other scenes that were preserved on the same reel.

Conclusion: Return to the Posthumous

Provisionally, I can summarize my findings about the posthumous as follows: one of the perceptual-experiential grounds on which the posthumous emerges is the growing prestige of images, and especially of moving images, in our general awareness of both past and present. The liveness, the evidentiary authenticity and presence, but also the uncanny undead-ness and untapped energies emanating from our photographic and cinematic archive have created powerful new forms of presence, where the agency of things and of images almost count as equivalent to that of people and individuals. This, too, emerges from the close reading of my father’s home movies, where presence and absence, on-screen and off-screen turn out to be potent vectors, reintroducing the nominally absent Leberecht Migge into the picture, and redefining the presence of both my mother and my grandmother, as crucial narrative agents, in a story that was supposedly about the architect of a Frankfurt building, itself made posthumous by an act of architectural vandalism, which, with hindsight, it is hard to know whether to be outraged by, or grateful for.

The historical-political ground in this particular case, however, is the massively posthumous presence of Nazism, the Holocaust, and the Second World War, under whose retroactive presence we still seem to live, or at least, under whose uncanny, traumatic, and often unexpected forms of posthumous agency, our current obsession with history and memory still plays itself out.

Martin Elsaesser, though not a victim of the Holocaust and only ignored by the Nazi regime rather than actively persecuted, has belatedly benefitted from this pervasive posthumousness: the City of Frankfurt – just like the ECB on their website – is now proud to be associated with the growing retroactive reputation of the architect Martin Elsaesser.

Furthermore, the last building that Elsaesser had a part in designing – the 1931 annex to the Palmengarten-Gesellschaftshaus and whose budget-overrun was used, at the time, as one of the excuses to get rid of him, has been carefully restored by the prestigious British architect David Chipperfield. This building entered the history books as the work of Ernst May, the architect generally associated with the New Frankfurt, and among the leading figures of International Modernism in architecture. I was therefore not a little surprised, when a newspaper article, ahead of the official reopening, captioned its picture with the words ‘Elsaesser-Anbau’ (‘Elsaesser-annex’), retroactively re-attributing ownership to my grandfather, and thus inadvertently undoing a past injustice, one depicted in a 1931 cartoon, sarcastically expressing the city’s Schadenfreude of finally having managed to send him packing.

In this sense, my father’s home movies and photographs captured a presence – life on the island – which may have nothing to do with Frankfurt or the ECB, but had hidden the differently tragic pasts of my mother and grandmother, and thus managed to preserve nonetheless the traces of things to come, in the sense that these images not only give added life to my grandfather’s claim to posthumous recognition, but their uncanny agency has projected me into several family histories, all now demanding to have a future in a media memory that only chance encounters, contingent conjunctures, and a posthumous constellation have even made thinkable.

Notes

Martin Elsaesser (1884–1957), German architect, author, and university professor. See [https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Martin_Elsaesser]; [http://www.architekten-portrait.de/ martin_elsaesser/].

Thomas Elsaesser, ‘Building Blocks for a Biography’, in Martin Elsaesser and the New Frankfurt, ed. by Peter Cachola Schmal, Thomas Elsaesser, Christina Graewe, and Jörg Schilling (Tübingen: Wasmuth, 2009), pp. 21–29.

Prominent voices of protest were the architecture critic Dieter Bartetzko, ‘Der EZB Neubau – Ein Euro-Krüppel’, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 21 February 2007, and the architect Christoph Mäckler [http://www.faz.net/aktuell/feuilleton/debatten/grossmarkthalle-frankfurt-zerstoerung-im-namen-der-avantgarde-1380634.html].

Jeremy Tambling, Becoming Posthumous: Life and Death in Literary and Cultural Studies (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001).

Tambling, Becoming Posthumous, p. 4.

See also Hermann Hipp and Roland Jäger (eds.), Haus K. in O. 1930–32. Eine Villa von Martin Elsaesser für Philipp F. Reemtsma (Hamburg: Gebrüder Mann, 2005); Thomas Elsaesser, Jörg Schilling, and Wolfgang Sonne (eds.), Martin Elsaesser, Schriften (Zurich: Niggli Verlag, 2014); and Elisabeth Spitzbart Jörg Schilling, Martin Elsaesser Kirchenbauten, Pfarr- und Gemeindehäuser (Tübingen: Wasmuth, 2014).

Thomas Elsaesser, ‘Die Stadt von Morgen: Bauen und Wohnen im nicht-fiktionalen Film der 20er Jahre’, in Der Dokumentarfilm in Deutschland: 1919–1933, ed. by K. Kreimeier (Stuttgart, Leipzig: Reclam, 2005), pp. 381–409.

Thomas Elsaesser, ‘Holocaust Memory as an Epistemology of Forgetting – Harun Farocki’s Respite’, in Harun Farocki Against What? Against Whom?, ed. by Antje Ehmann and Kodwo Eshun (London: Koenig Books, 2009), pp. 57–68.

Hannah Arendt, ‘Introduction’, in Walter Benjamin, Illuminations (London: Jonathan Cape, 1970), pp. 1–51 (p. 3).

Thomas Elsaesser, ‘Die Geschichte, das Obsolete und der found footage Film’, in Ortsbestimmungen: Das Dokumentarische zwischen Kino und Kunst, ed. by Eva Hohenberger, Katrin Mundt (Berlin: Vorwerk 8, 2016), pp. 135–155; and Thomas Elsaesser, ‘Film Heritage and the Ethics of Appropriation/Filmskabastinaietikaprisvajanja’,in Muzejfilma – Film u Muzeeju (Informatica Museological 47), ed. by in Lada Drazin Trbuljak (Zagreb: MDC, 2017), pp. 6–13. Also published as: ‘La ética de la apropiación: El metraje encontrado entre el archivo e internet’, in [http:// foundfootagemagazine.com], ed. by César Ustarroz and as ‘Zur Ethik der Aneignung: Found Footage’, (Berlin-DokuArts: Fachtagung ‘Recycled Cinema’, Zeughaus Kino, Berlin 11 September 2014) [http://doku-arts.de/2013-14/content/sidebar_fachtagung/Thomas-Elsaesser.pdf].

See for instance, Aleida Assmann, Cultural Memory and Western Civilization: Functions, Media, Archives (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012) and Thomas Elsaesser, German Cinema – Terror and Trauma: Cultural Memory since 1945 (New York: Routledge 2015).

Pierre Nora, Les lieux de mémoire (Paris: Gallimard, 1984–1992).

Marina Warner, ‘What are Memory Maps’, [http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/m/ memory-maps-about-the-project/].

Thomas Elsaesser, ‘Media Archaeology and the Poetics of Obsolescence’, in At the Borders of Film History, ed. by Alberto Beltrame, Giuseppe Fidotta, and Andrea Mariani (Udine: Gorizia Film Forum, 2014), pp. 103–116.

Mikhail Bakhtin, ‘Form of Time and Chronotope in the Novel’, in The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays, ed. by Michael Holquist (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1981), pp. 84–258.

See Andrew J. Webber, Berlin in the Twentieth Century: A Cultural Topography (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011).

In what follows, I have chosen to engage in an extended dialogue with Roger Odin. Not only is he the writer who has thought more systematically and penetratingly about home movies than anyone I know, he is also a friend and colleague – with whom I once had a memorable discussion regarding home movies. Odin’s major publications on the topic are: Roger Odin (ed.), Le film de famille usage privé, usage public (Paris: Meridien-Klincksieck, 1999); Roger Odin, ‘Ch 5: Espace de communication et migration: L’exemple du film de famille’, in Roger Odin, Les espaces de communication (Grenoble: Presses Universitaires des Grenoble), pp. 103–122; Roger Odin, ‘Reflections on the Family Home Movie as Document: A Semio-Pragmatic Approach’, in Mining the Home Movie: Excavations into Historical and Cultural Memories, ed. by Karen Ishizuka and Patricia Zimmerman (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), pp. 255–271; Roger Odin, ‘The Amateur in Cinema, in France, Since 1990: Definitions, Issues, and Trends’, in A Companion to Contemporary French Cinema, ed. by Alistair Fox, Michel Marie, Raphaëlle Moine, and Hilary Radner (Oxford: Wiley Blackwell, 2015), pp. 590–610.

Roger Odin, in Mining the Home Movie, p. 261.

Scholarly interest in amateur film-making and home movies has grown substantially in the last decades. Besides Odin, Patricia Zimmerman has been a major pioneer: her Reel Families: A Social History of Amateur Film (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1995) was followed by Karen Ishizuka and Patricia Zimmerman (eds.), Mining the Home Movie: Excavations into Historical and Cultural Memories (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007). Other important collections are Laura Rascaroli, Gwenda Young, and Barry Monahan (eds.), Amateur Filmmaking: The Home Movie, the Archive, the Web (New York and London: Bloomsbury, 2014) and two monographs in German: Alexandra Schneider, Die Stars sind wir: Heimkino als filmische Praxis (Marburg: Schüren, 2004) and Martina Roepke, Privat-Vorstellung: Heimkino in Deutschland vor 1945 (Hildesheim: Georg Olms Verlag, 2006).

Roger Odin, in Companion to French Cinema, p. 591.

Roger Odin, in Companion to French Cinema, p. 592.

What also struck me is how, in the scene shot among the boats in the lake, my father must have stood in the water with his precious camera, even using expensive and rare colour stock, to film the mixed company ducking and diving in the waves of the lake, so close to the water level that one is almost afraid of the water ruining the camera. What must have been exhilarating is the extreme mobility of the handheld device, comparable to today’s camcorders or mobile phones. The Cine-Kodak had a clockwork wind-up mechanism: no need for a battery or any other electric source.

See the conference ‘Activating the Archive: Audio-Visual Collections and Civic Engagement, Political Dissent and Societal Change’ held at the EYE, Amsterdam, 26–29 May 2018 [https:// www.eyefilm.nl/themas/eye-international-conference-2018].

Roger Odin, in Mining the Home Movie, p. 262.

Jacques Rancière, The Politics of Aesthetics (London: Continuum, 2004), pp. 9–46.

Here and elsewhere, I use home movies and amateur film as if they were interchangeable, ignoring that there is a body of writing that tries to draw clear distinctions. For Liz Czach, for instance, amateur films tend to be evaluated for their aesthetic qualities and technical ambitions, while the generally less technically accomplished home movies are appreciated for their cultural or historical significance. ‘Home Movies and Amateur Film as National Cinema’, in Amateur Filmmaking: The Home Movie, the Archive, the Web, ed. by Laura Rascaroli, Gwenda Young, and Barry Monahan (New York, London: Bloomsbury, 2014), pp. 27–37. The hermeneutics I am proposing can apply to both but may seem to favour the home movie. See also Carlo Ginzburg, as well as symptomatic reading for structuring absences, and ‘the dogs that did not bark’ theory, which takes me to ‘media archaeology’.

The term ‘unwitting testimony’ comes from Arthur Marwick: ‘from at least the time of Frederick Maitland (1850–1896), historians have been using unwitting testimony to establish the beliefs and customs of past societies’. [https://www.history.ac.uk/ihr/Focus/Whatishistory/ marwick1.html].

I take the phrase from Karen Shopsowitz, director of My Father’s Camera, quoted in Catherine Tunnacliffe, ‘Filmmaker re-appraises home movie’, Eye vol. 10 issue 30 (5 March 2001).

Patricia Zimmerman, ‘Morphing History into Histories: From Amateur Film to the Archive of the Future’, Mining the Home Movie: Excavations in History and Memory, pp. 276–277.

Roger Odin, Les espaces de communication, p. 108. Odin goes on to praise Peter Forgacs for using extensive post-production (sound, music, commentary) in order to turn this authenticity effect into a reflexivity mode: ‘In the Bartos family, the use of family films, far from blocking the question of truth, places it at the heart of the film, but it took a lot of cinematographic work to achieve this result. The task involved analyzing the family film as an ideological operator that reveals the behaviour of a class – here the European bourgeoisie’s indifference or obliviousness to fascism.’ Roger Odin, Les espaces de communication, p. 114.

Roger Odin, in A Companion to Contemporary French Cinema, (p. 592).

See, for instance, ‘Lifestyle Propaganda: Modernity and Modernisation in Early Thirties Films’, in Thomas Elsaesser, Weimar Cinema and After (London: Routledge 2000), pp. 420–443, and Thomas Elsaesser, ‘Propagating Modernity: German Documentaries from the 1930s: Information, Instruction, and Indoctrination’, in The Oxford Handbook on Propaganda, ed. by Jonathan Auerbach and Russ Castronovo (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), pp. 233–256.